The Scottish economist and philosopher, Adam Smith, is a huge favourite of economists, and especially economists who believe that the best way to deliver progress and prosperity is through the free market. Writing in 1776 at the time of the American, French and industrial revolutions, he most famously said that if people are left at liberty to pursue their own rational self-interest, that this ‘invisible hand’ will lead to the best outcomes for society as a whole.

The Adam Smith Institute, a right-wing think-tank set up in his honour, is our nemesis every year when we release Oxfam’s Davos report on inequality. I have been in lots of debates with their representatives over the years, where they question the importance of worrying about inequality, and especially taxation, and instead explain that the answer is simply more free markets.

Interestingly this was not all Adam Smith said though. He is very selectively quoted. Unlike many modern economists who prefer theoretical mathematical models that abstract from reality, Smith was an empiricist, observing not just the UK economy (which at that time was very similar in shape to many countries in the Global South today) but also other countries all over the world. He made use of what concrete data he could get to help support his theories.

Class warrior Smith

In doing so, he was one of the first economists to theorise the idea of social classes to help understand the economy, dividing society into workers, landlords and capitalists. He also had a very low opinion of rich people, seeing them either lazy or indolent, living off the rents from their land, or as monopolistic, rapacious capitalists.

He was the first economist too to introduce the idea that the prosperity of a nation should be measured on how well the working majority are doing, and whether their lives are becoming measurably better, rather than only measuring the opulence of the richest.

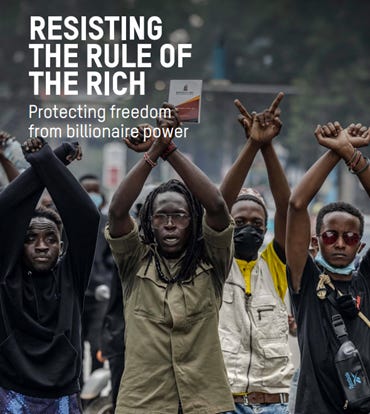

Because of this I actually think he would have liked Oxfam’s Davos paper this year, Resisting the Rule of the Rich, which is about the dangers of economic power turning into political power, and the suppression of liberty and freedom for the many to protect the wealth of the few. He was deeply concerned about the influence of rich capitalists over politics and government policy, and he felt that if they were allowed to pursue their self-interest in this way this would run contrary to the common interest. That this would in fact be a very visible hand, and would instead lead to increasing monopoly power.

Anti-colonial Smith

This led him to be very negative about colonialism. He was opposed to the companies like the East India company that used their monopoly power to colonise and oppress other countries and reap huge profits, so he would probably have liked our Davos paper last year on colonialism too.

He was not a fan of big government either. He felt that governments were a very poor substitute for the free market. Branko Milanovic (whose brilliant book, Visions of Inequality inspired this blog) reckons Smith’s state would represent about 10% of GDP, whereas modern welfare states are more like 40% of GDP. There we would definitely disagree. I think that modern, accountable welfare states, using progressive taxation to provide universal free healthcare or education, and protecting the young, the old and those who are struggling, are one of the greatest thing humans have ever invented.

Smith believed that competition was the best way of regulating capitalists, and not government, as government can be captured by the rich and powerful – something he saw all the time. Politicians can be captured by wealth and money; that is as true today as it was in the 18th century. His answer to this though was to keep government as small as possible. The trouble is I think that regulation of the market by a small government is likely to be very weak as they have very limited economic power to face up to rich capitalists. This surely leaves the capitalists free to conspire and form monopolies even more. For me, modern, accountable states that answer to the people and not to organised money are the best way to counterbalance the power of capital; rather than shrinking a state that is captured, we should be capturing it back.

Anyhow, given the focus of our Davos paper this year on civil and political freedoms and inequality, I began to wonder what kind of a foreword Adam Smith might have written for the paper, and I have assembled the following from his writing:

Wherever there is great property, there is great inequality. For one very rich man, there must be at least five hundred poor, and the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many.

As soon as the land of any country has all become private property, the landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and demand a rent even for its natural produce. The wood of the forest, the grass of the field, and all the natural fruits of the earth, which, when land was in common, cost the labourer only the trouble of gathering them, come, even to him, to have an additional price fixed upon them. [yes Smith, and not Karl Marx wrote this!]

What improves the circumstances of the greater part can never be regarded as an inconveniency to the whole. No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable… If [justice] is removed, the great, the immense fabric of human society, that fabric which to raise and support seems in this world if I may say so has the peculiar and darling care of Nature, must in a moment crumble into atoms.

The mean rapacity [of]… merchants and manufacturers ... [shows that they] neither are nor ought to be the rulers of mankind. People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices…The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order [of people], ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men, whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.

In the courts of princes, in the drawing-rooms of the great, where success depends not upon merit but upon favour, truth is seldom heard. This disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful… is the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments. [I can’t think of a better description of Davos.]

One feels we must all combine to resist the rule of the rich in our society.’

[Ok I wrote the last sentence, but the rest is direct quotes I promise]

ENDS

Author: Max Lawson, Head of Inequality Policy at Oxfam International and EQUALS podcast co-host. He is also a visiting Professor in Practice at the LSE International Inequalities Institute and the co-chair of the Global People’s Medicines Alliance.

If only those right-wing think tankers, who worship Smith, would read all his work - including the Theory of Moral Sentiments. Inconvenient subject matter, ethics. Smith's "impartial spectator" would make mincemeat of them.