Banking on inequality

Demystifying the relationship between decisions made at central banks and inequality.

Jordi Schröder Bosch, an economist at Positive Money Europe, joined us on the latest episode of the Equals podcast to talk about the impacts of monetary policy on inequality. It was a fascinating conversation that challenges the myth of central bankers as just technical, apolitical bean counters.

Anyone who cares about inequality should pay attention to monetary and fiscal policy ―because the levers pulled by both politicians and central bankers can either widen or reduce inequality. In fact, the political independence of many central bankers often aligns them more closely with financial markets and the interests of the richest, who own the bulk of financial assets.

In this week’s Bulletin, we break down what Jordi had to say about the role of central banks in shaping inequality.

Central bank-induced inequality

How money flows is a reflection of how power flows. For decades, there has been a strong trend toward separating monetary policy (i.e., decisions about how much money circulates in the economy) from politics ―this has meant having independent central banks, run by unelected technocrats. In many countries in the Global South, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a global unelected institution, also has huge power over monetary policy. Yet these decisions are far from technical, and they all have important distributional impacts, that can either increase or decrease inequality.

In whose interest? Most central banks focus primarily on keeping inflation low ―a choice that is deeply political, even if often framed as technical. The U.S. Federal Reserve stands out as an exception by also having a mandate to pursue maximum employment, unlike many other central banks. While it is true that high and persistent inflation tends to hurt ordinary people ―by raising the prices of essentials― targeting very low inflation isn’t necessarily ideal, especially if high interest rates result in more unemployment or a recession. By putting up interest rates to slow the economy and lower inflation, central banks are making incredibly important decisions that will impact the lives of ordinary people, yet they do this largely outside of democratic oversight.

Central banks are also very close to financial markets, as their decisions have very big impacts on the cost of borrowing ―and without political oversight, the power and influence of markets over central bank “technocrats” is not counterbalanced. Financial markets are dominated by the assets of the rich, with 43% of all financial assets being owned by the richest 1%.

Quantitatively easing the rich even richer. After the 2008 financial crisis, interest rates were cut as low as they could go, so central banks started printing money, and used that to buy debt. Trillions were pumped into the economy this way, both during and after the financial crisis, and again during COVID-19. In both cases, the explosion in the amount of money in the world led to a sharp increase in the price of assets, whether this was property, stocks and shares, or gold. This was a bonanza for billionaires and the richest. Their fortunes skyrocketed overnight ―not because of anything they had done differently― but because of the action of central banks. This makes a powerful case for higher taxes on wealth to claw back windfall profits from private hands and put it to public use instead.

Helicopter money. Central banks decide who gets bailed out and who doesn’t ―another hugely political decision. After the financial crisis, central banks printed money to buy debt, freeing banks to lend more and get the economy going again. In doing so, they bailed out the very banks that had caused the crisis in the first place. They didn’t have to choose this path. Instead, as proposed by many economists, they could have given money directly to ordinary people. Depositing $2,000 dollars in everyone’s bank account, for example, could have boosted the economy and helped everyone who was struggling.

This is closer to what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, when central banks in many rich countries supported government efforts to help people directly. This was a good thing, as it helped reduce income inequality in some rich countries, but it simultaneously drove up wealth inequality as asset prices exploded.

The dollar dominates. Central banks also contribute to inequality between the Global North and the Global South. They are very hierarchical, with the U.S. Federal Reserve sitting at the top, and the decisions they make reverberate around the world. For example, if the Fed increases interest rates, then countries (especially in the Global South) have to increase their interest rates to stop money flowing out of their economies and into the dollar. It also drives up the cost of paying debts that are denominated in dollars, and countries in the Global South are much more likely to have debts in dollars.

Who to swap with? The U.S. Federal Reserve, during times of crisis, agrees to liquidity swaps with central banks of allies, like Japan, the UK, or the European Union. This means their currencies are effectively backstopped by the dollar, which is the world’s principal reserve currency. This is of huge benefit to those countries but also helps global financial stability. It is done when countries are facing financial instability but swaps are only an option for a club of rich countries, usually ignoring countries in the Global South. This backstop means the cost of borrowing is much lower in rich countries than in the countries of the Global South.

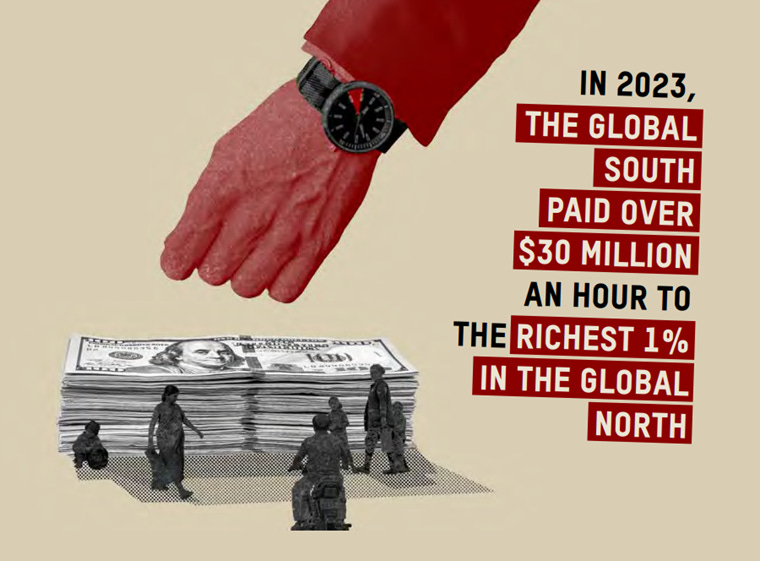

Sucking money from the Global South to the rich in the Global North. Researchers from the World Inequality Lab have found that this lower cost of borrowing gives a huge advantage to the wealthiest people in rich countries who can borrow at very low costs and channel it into profitable investments in the Global South. In Oxfam’s latest annual inequality report, we calculated that this imbalance alone leads to a payment of almost $1 trillion a year from the Global South to the Global North, of which $30 million an hour is being paid to the richest 1% in rich countries.

The alternative. Positive Money Europe gives some interesting policy ideas as alternatives to the inequality reproducing model of today’s central banks. For example, interest rates could be lower for things essential for a green transition and higher for fossil fuels. Quantitative easing could be targeted at sectors that need investment, like renewable energy. During financial emergencies, rather than bailing out just banks, helicopter money could be used to pay deposits directly to people who need it.

Beyond specific policies, the key point is that the actions of central banks have huge distributional implications and impacts on national and international inequality, that the decisions they take are deeply political and far from simply technical and Positive Money also thinks they should be subject to more democratic oversight and control.

Something to read/listen to

Europe’s Billionaire Problem - Social Europe: How the Billionaire Boom Is Fueling Inequality—and Threatening Democracy

Climate Equality- Article in Nature High-income groups disproportionately contribute to climate extremes worldwide - If all of the world's population had emitted as much as the top 0.1% since 1990 then the global mean temperature would be 12.2°C higher today. If everyone emmitted as much as the top 1% the temperature would have increased by 6.7°C

RIP Jose Mujica- The best (translated into English) quotes from the wonderful Jose Mujica, former Guerrilla fighter and President of Uruguay.

“Life is a beautiful adventure and a miracle,” he said. “We are too focused on wealth and not on happiness. We are focused only on doing things and, before you know it, life has passed you by.”