France, 2018. The country is paralysed by a huge series of protests against moves by President Macron to raise green taxation on fuel, whilst simultaneously abolishing the wealth tax on the super-rich. The protestors become known as the ‘Gilet Jaune’ or Yellow Vest movement. Such is the fury that the President is forced to reverse the increase in fuel duty. Climate policy-making at its most class-blind, this high-handed move spectacularly backfires.

As Europe is crippled by high gas and energy prices this winter, there are some who have been saying that this is an opportunity to speed a green transition, a kind of shock treatment to get us all somehow ‘used’ to high energy prices and forced to consume less.

Given the suffering these dramatic increases in prices are inflicting on poor people across the continent, forcing many to choose between heating and eating, such hairshirt sentiments seem very brutal to me. I suspect they are rarely made by those who themselves will struggle to pay their heating bill.

It is also, I think, a bit politically crazy. It seems to me we will only be able to deliver the dramatic transformation in our economies needed to stop climate change if all of society agrees and believes it is the right thing to do. It can’t be forced onto people like a dose of cod liver oil. Instead, there is a huge risk that climate action becomes identified with a patronising, liberal elite and is lambasted by right wing populists everywhere, speeding our planet faster towards disaster.

At the root of this is the failure to properly see climate change as a class issue. Instead, the issue is almost always seen in terms of different nations, the rich world versus the developing one. If personal emissions come into it, then they are invariably simply per capita averages for each nation.

It is true that everyone in rich countries needs to reduce their carbon emissions, whether rich or poor. But national averages obscure as much as they inform. Fortunately, new analysis by a handful of actors, which looks at the carbon emissions of different income groups, and in particular the emissions of the top 10% and top 1%, is gaining traction.

What the data shows is appalling. Climate breakdown is being caused hugely by the richest class in every country. They’re the ones who are recklessly driving us over the precipice of planetary breakdown.

Oxfam analysis with the Stockholm Environment Institute found that globally:

The per capita emissions of someone in the top 1% is 100 times higher than someone in the bottom 50%, and 35 times higher than the target for 2030.

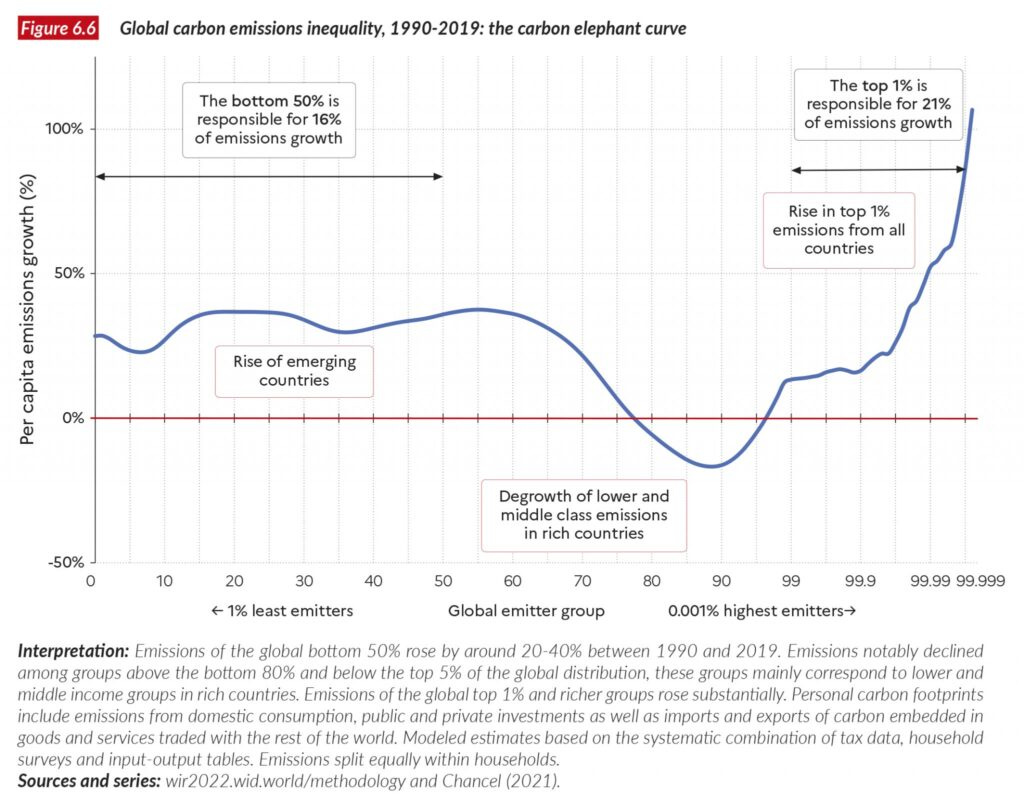

Since 1990, the richest 5% were responsible for over one third of the growth in total emissions. The top 1% were responsible for more than the whole of the bottom 50%.

For about 20% of the human population – and that corresponds to the working and lower middle classes in rich countries mainly – per capita emissions actually fell from 1990 to 2015.

Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty carried out a very similar analysis which the above diagram represents. You can see the dip for those in the global distribution that correspond to the working and lower middle classes in rich nations. Their emissions remain too high to be in line with climate targets, but it is notable that they were the only group whose emissions fell.

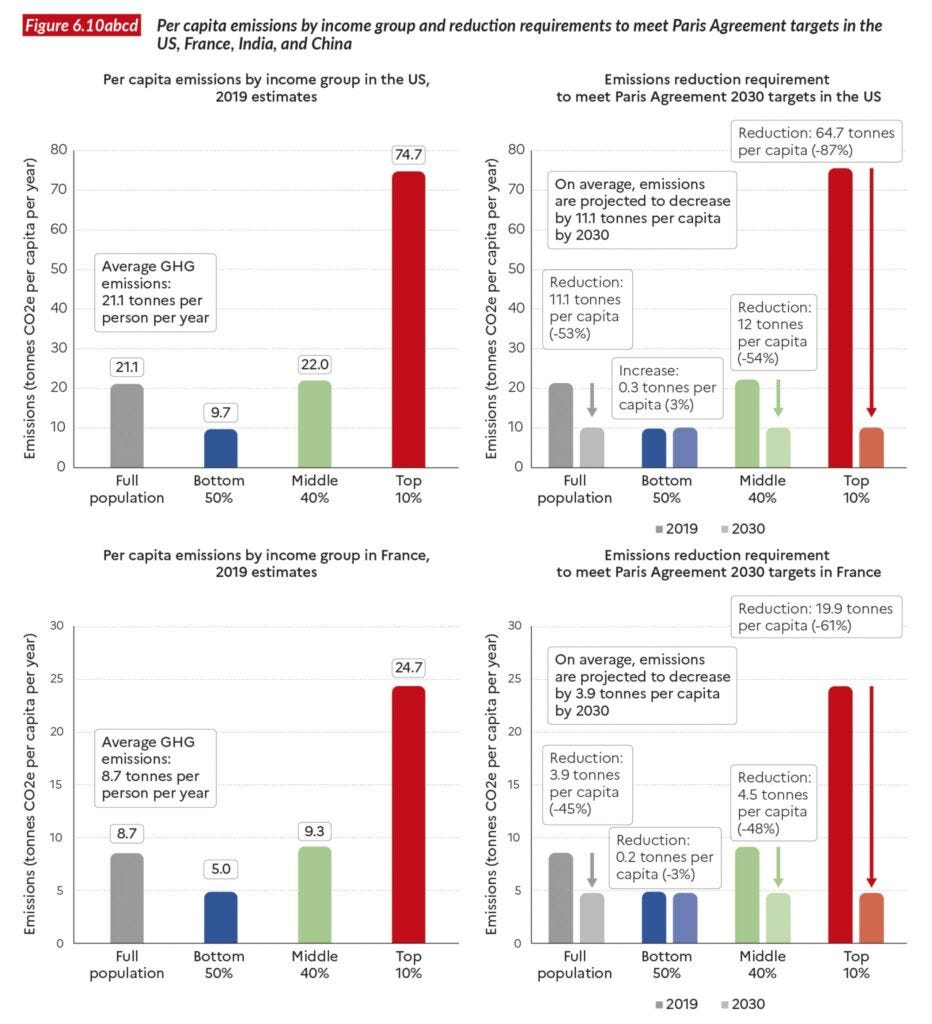

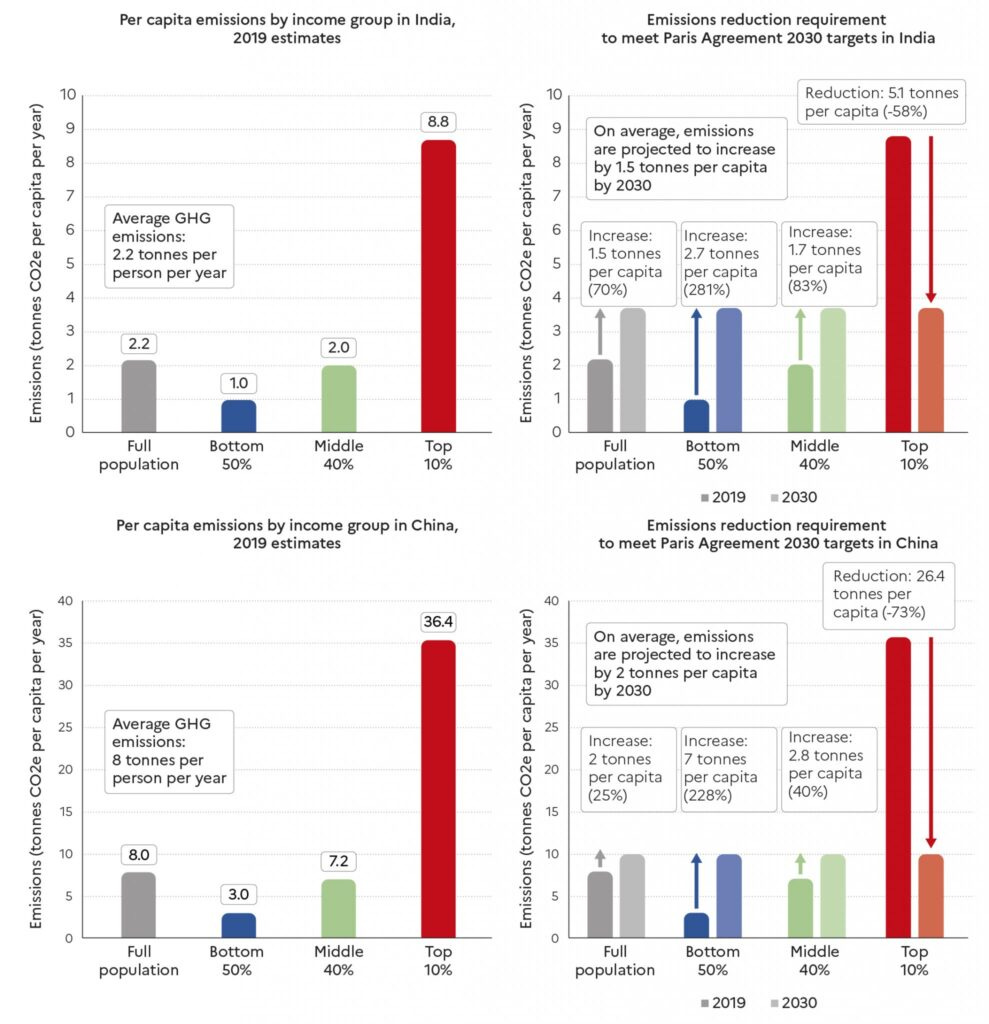

The richest 10% globally are mainly to be found in rich countries, but not exclusively. Yet the inequality in emissions is replicated at national level in rich countries too. Nationally, the emissions of the richest 10% dwarf those of the rest of the income distribution, whether you are in France or India (see graphs later on).

Other studies have also begun to look at microdata on the “carbon lives” of the very richest. One study looked at the emissions of 20 of the world’s richest billionaires found that each produced on average 8000 tonnes of carbon dioxide – for comparison, the average citizen in a rich country is around 6 tonnes and the amount needed to hit the 1.5 degrees global safety target is just over 2 tonnes per person. New analysis of the private jet flights of the super-rich has also revealed the celebrities and billionaires emit more carbon in minutes than ordinary people do in a year.

Not only are the emissions of the rich incredibly high and growing, but the nature of their emissions are also completely different. For the richest people, most of their emissions come from their investments, up to 70%. This mirrors inequality as a whole. For almost all of society, their primary income is from work, but for the richest it is from the return on their capital. The lifestyle emissions of a billionaire might be a thousand times higher than average, but their investment emissions can be a million times higher. We have exciting new analysis of billionaire investment emissions we are working on which we will publish in November ahead of this year’s UN Climate COP.

People near the bottom of the income scale often do not have a lot of choice over their carbon emissions. They may be living in poorly insulated rental housing or have to drive to work because of inadequate public transport. As in every other aspect of life, the richer you are, the more choice, the more agency you have to change your life. This applies to your lifestyle consumption emissions, but even more so to your investment emissions. You get to choose where you invest your money. Given this the continued bankrolling of fossil fuels and polluting industries is by the very rich, to my mind, completely indefensible.

At Oxfam of course, our primary concern is with those in the poorest half of society, in every county, but particularly in countries in the Global South. We want everyone on earth not just to have what it takes to survive, but what it takes to thrive. That everyone has a right to safety, a decent income, good home, free public healthcare, schools, public transport, parks. Every family should have a fridge, a television. Everyone should have access to a smartphone, a computer and the internet.

The fear of many is that if we did do this, and enabled all 8 billion of us to live a decent life, that will rapidly overshoot the natural carrying capacity of our planet, not just in carbon but so many other planetary boundaries too.

This fear of growing populations in the Global South often used to shift the blame onto developing countries too. That while the fault of carbon emissions may have historically been with rich nations, it is now the billions of Chinese and Indians that we must worry about (to say nothing of the billions more waiting behind them).

What the analysis above shows categorically is that the hundreds of millions that have escaped poverty globally in the last 20 years are only a small part of the dramatic increase in emissions. In fact, nearly half of the rapidly accelerating growth in total emissions – and the attendant rise in climate crisis risks and damage – has not occurred to the benefit of the poorer half of the world’s population, it has instead merely allowed the already wealthy top 10% to augment their consumption and enlarge their carbon footprints.

Nevertheless, it does seem true if we were to stay at current levels of inequality then, in order to deliver a decent life for all, global GDP growth would have to increase way beyond our planet’s ability to sustain it. Over the last 40 years, every dollar in global GDP growth has seen 46 cents go to the top 10%, and only around 9 cents go to the bottom half of humanity. The bottom 10% of humanity received less than 1 cent of every dollar in global income growth.

This distribution is so insanely unfair and inefficient that to lift all of humanity above the poverty line of $5 a day would need the global economy to be 173 times bigger than what is it. That’s an environment impossibility.

Does this mean that the goals of planetary survival and a decent life for all are incompatible? That to save our planet the majority of humanity must stay forever poor and hungry? Not necessarily. Everything instead I think depends on the level of inequality.

It is well studied that people all over the world, when asked how unequal their countries are, consistently and massively underestimate the scale of the divide. It is also the case that when asked for their preferred level of ‘fair inequality’, whilst this differs between societies, the majority consistently want their society to be a lot more equal than it actually is.

A recent study in Nature took these inequality preferences and combined this with the carbon emissions required for everyone on earth to have decent living standards. They found that if societies worldwide actually matched what their citizens felt was a level of ‘fair inequality’ then it would be possible for all of humanity to have a decent living and stay within the energy limits to prevent 1.5 degrees of global heating.

It seems to me that the evidence is pretty clear that the richest people in our society are a huge part of the problem, through their unsustainable luxury lifestyles and critically their investments bankrolling of a fossil fuel economy.

We can also see that a massive reduction in inequality is the only way that everyone on earth can live a decent life and guarantee the future of our planet.

Once you start looking at the emissions of different income groups, and the nature of those emissions, it has the potential to transform climate policy making. To maintain any level of fairness, the richest must make by far the biggest cuts in their emissions. This is true in rich countries and in developing countries too. As this diagram from Chancel and Piketty shows for the US, France, China and India:

This means for example we should have not a flat carbon tax but a progressive carbon tax. The more carbon you use, the higher the tax you pay. Polluting investments should have additional punitive taxation put on them or, better still, simply be banned. Luxury goods, private jets, all should be heavily taxed or heavily restricted. Every national action to tackle climate should be done progressively, in ways that make the richest, highest emitters shoulder most of the cost and in turn contribute to increasing equality, not inequality.

General increases on the richest and on wealth, as well as other moves to rapidly reduce inequality, also take on a whole new climate imperative. It is clear I think that our planet simply cannot afford the very rich. As the writer George Monbiot has said, ‘we need to make extreme wealth extinct: it’s the only way to avoid climate breakdown.’

Author: Max is the Head of Inequality Policy at Oxfam International & EQUALS Podcast co-host. He is also Co-Chair of the global People’s Vaccine Alliance.