I remember on my first visit to Vietnam with Oxfam in 2003, staying at a small colonial era hotel in the old town in Hanoi, where there were just a few guests. Every morning, we would be given a small fresh baguette and as many cups of strong black coffee as we wanted. It was my first time drinking Vietnamese coffee, which has a lovely flavour, with hints of cherry in the background, and I was totally hooked.

The year before I had helped a bit with the team working on a report we were writing about the global crisis in the coffee market, where prices had fallen to a thirty-year low. The report had a great title, ‘Mugged: Poverty in your coffee cup’. Here I learned that part of the reason that the coffee market was in trouble was because of the fact that Vietnam, in the space of a few years, had gone from not producing coffee at any significant scale, to being the second largest producer in the world, flooding the world market. This, combined with the wholesale liberalisation of the global coffee market and the capture of almost all the value by coffee roasters based in the Global North was having a terrible impact on coffee farmers.

The East German Coffee Crisis

At the time I remember someone saying that Vietnam’s decision to enter into coffee production was linked to the Eastern Bloc, but I only learned the full story recently. In East Germany in the late seventies the country was experiencing a huge economic crisis, a knock-on effect of the energy price shocks. Their problems were made harder because they had to find hard currency for imports from outside the Eastern Bloc countries, and one of the most important of these was coffee. East Germans were huge coffee drinkers, and access to coffee was a huge part of national culture, and a symbol of the success of the communist system. East Germans spent more on coffee than they did on furniture. This meant coffee had to be rationed, and mixed with chicory and other things, which was hugely unpopular. It was a national crisis.

They needed to find a solution to this crisis within the socialist world, and so the East Germans worked out a deal to address this with their socialist comrades in Vietnam. At that time Vietnam had just emerged from the Vietnam war, and although victorious, their economy was in a parlous state, and over 3 million people had died. They needed help.

Coffee comrades

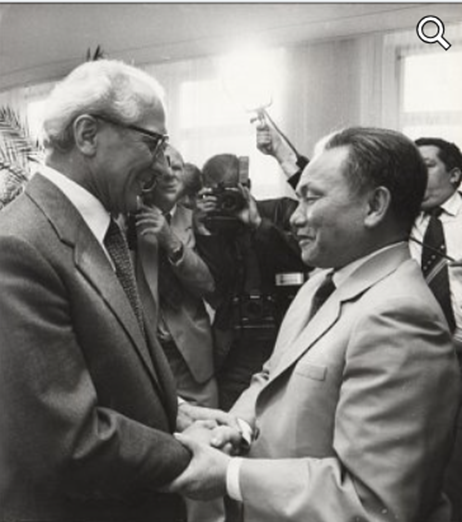

In 1977, Erich Honecker, the leader of East Germany visited Hanoi, and a development treaty was signed in 1980. A key part of this was to help Vietnam become a significant coffee producer. A huge area, 10,000 hectares was cleared in Dak Lak province. Workers moved there, and machinery, roads, and infrastructure were put in place and a new hydroelectric power plant built. East Germany sent lorries, farm machinery and equipment and helped build irrigation systems. Over 6000 coffee trees, including new breeds cultivated in Leipzig, were planted. The agreement was that in return for this big infusion of aid and expertise, Vietnam would export half of their coffee to East Germany for the next 20 years, sating the East German’s desire for coffee without the need for hard currency and helping to rebuild Vietnam.

Coffee bushes take between 4-7 years to fully mature, and this meant that by the time Vietnam was ready to export coffee to East Germany in early 1991, the Berlin Wall had fallen, and the Eastern Bloc was crumbling. So this large-scale socialist coffee swap never took place but was instead overtaken by history.

A development success story

Nevertheless, it was big development success for Vietnam. They produce 17% of the world’s coffee, or 30 million bags. The coffee industry exports about $4 billion worth of coffee and supports the livelihoods of 1.4 million smallholder farmers. A reunified Germany is the biggest export market.

Coffee farmers still struggle with poverty, with 25% of workers earning less than the minimum wage. Vietnam, like other coffee producing countries struggles to break into the lucrative roasting and packaging element of the coffee value chain which is still dominated by the Global North. But nevertheless, coffee production in Vietnam remains a really successful example of development, driven by the shared interests of two socialist nations.

Bittersweet influences

Coffee is not just for export, it is now huge in Vietnam too, with a very strong interest from the younger generation, born long after the days of East Germany. There are loads of super stylish new coffee shops, catering to Gen Z being opened by young entrepreneurs. Coffee has become associated with creativity, social expression and the ambitions of this new generation.

Interestingly, when you visit one of the many coffee houses in Hanoi, you will discover something else unique about Vietnamese coffee, which is their habit of drinking it with condensed milk, the super sweet milk that you get in tins. Their iced coffee version of this is absolutely delicious.

Condensed milk was originally introduced by French colonists and was also a part of the K rations given to US soldiers during the Vietnam war.

So, a Vietnamese cup of coffee is truly a product of communism, colonialism and capitalism, with the East Germans having a far more constructive record in the history of that wonderful country than either the French or the USA.

(Thanks to Hoa and Duong for help with this blog. You can listen to a good interview with the East German who led the coffee project, now 1995, here on BBC Witness History. The idea for this blog came from the brilliant book, Beyond the Wall by Katya Hoyer- you can watch a great podcast interview with her here.)

ENDS.