I have been passionate about fighting inequality since I was a child. I grew up in Africa, where the inequality between whites and blacks was shocking – and in some countries the black post-colonial elite were repeating the sins of their former colonial masters.

My pro-apartheid grandfather then forced us to return to South Africa in the worst days of apartheid, when black children were forced to live with their grandparents in the “homelands” (the least fertile bits of desolate land), and only blacks of working age were allowed anywhere near the whites. But a woman who worked in our block of flats had smuggled her son who was same age as me (eight) into the building, and we used to play together. One day, a gang of white teenage thugs decided it would be fun to throw bricks and rocks at us, and try to stone us to death. Thank God my aunt showed up and stopped the police arresting – not the thugs, but my friend for being in white area!

When I came back to Britain, I also saw institutionalised inequality. My mother had to travel round the country for work and enrolled me briefly in a private school before I went to a government school. I saw how the “school apartheid” in the UK which continues to this day. Wealthier children who are no brighter than poorer ones still get most of the highest-paying and most powerful jobs, perpetuating inequality through the generations.

At university, I realised that debt injustice was wrecking the lives of billions of people. My PhD became a book called The Crumbling Façade of Africa’s Debt Negotiations: Chaos, Arrogance and Secrecy. It traced how because creditors held 100% of power in secret debt negotiations, they decided the amount of debt relief based on the position of the most recalcitrant creditor, leading to a chaotic system where countries came back repeatedly for relief, while cutting spending on the things their people really needed – education, food, health and water.

I realised that debt was inextricably linked with poverty and inequality. Some borrowing was essential – helping to fund all the things citizens want and need; but when countries ran out of money to pay it back, they faced a debt crisis and ordinary citizens paid the price. The creditors (external or domestic) are nearly all rich, dominated by financial institutions and people making money out of wealth they hold in financial investments. On the other hand, those who pay the biggest price in a debt crisis are poor and middle-class citizens who see “austerity” - spending cuts in education, health, social protection, and public sector wages; and tax increases - to repay the debt. When there is a debt crisis, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

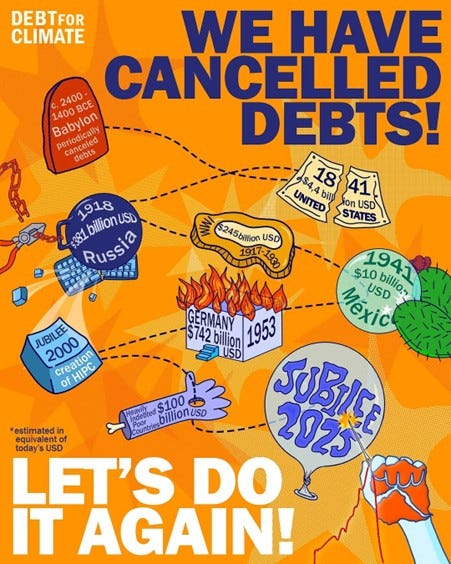

In the 1990s/2000s, I was at the centre of the fight for debt relief, advising the Jubilee debt cancellation movement and helping global South countries (the group known patronisingly as Heavily Indebted Poor Countries) to fight their case to negotiate maximum debt relief. We achieved a huge amount – including getting creditors to bring debt payments down to 10% of budgets. This allowed countries to double or treble social spending – providing free primary education to all children and saving millions of lives. In countries like Rwanda, governments invested in rural roads and small markets to create sustainable livelihoods for the poor. These efforts set up those countries for a decade of strong growth and poverty reduction.

How did we do it ? By combining a massive popular Jubilee campaign movement, analysis coming up with workable and affordable solutions. and tough lobbying by the beneficiary countries (evaluators later said they achieved US$27 billion of the US$100 billion cancelled).

Lots of people object to debt relief on the grounds that the countries are corrupt. It is true that corruption by lenders and borrowers is frequent – I and many others have been threatened with violence by the crooks when we have investigated them. To stop it we need strong laws at both ends. The UK anti-corruption law of 2010 was used by Mozambique in 2025 to help spare its citizens from having to pay US$2 billion of crooked loans, and many other countries need to strengthen their laws to cover debt contracts. Also vital is transparency and accountability to citizens and parliaments of the global South, not just by publishing data and contracts online, but through national accountability processes supported by capacity-building for parliaments and citizens to stop bad deals, and for government officials to produce the analysis citizens need. Last time, to ensure the proceeds of debt relief were spent, there was a revolution in accountability: countries designed their own Poverty Reduction Strategies, with strong citizen participation, and then committees of government, civil society and development partners oversaw the spending: that’s why the debt relief achieved so much development progress.

On the other hand, the big thing we didn’t achieve was to change the system. The creditors remained in charge, and decided by 2010 to abolish almost all the advances of the 2000s, and go back to decisions based on financial not development criteria. When in around 2015 creditors began to cut grant aid, and push countries to borrow in financial markets, just when the world had set new development goals which required trillions of dollars of financing, I could see that we were heading for a new debt crisis: and now we are in the worst crisis in history.

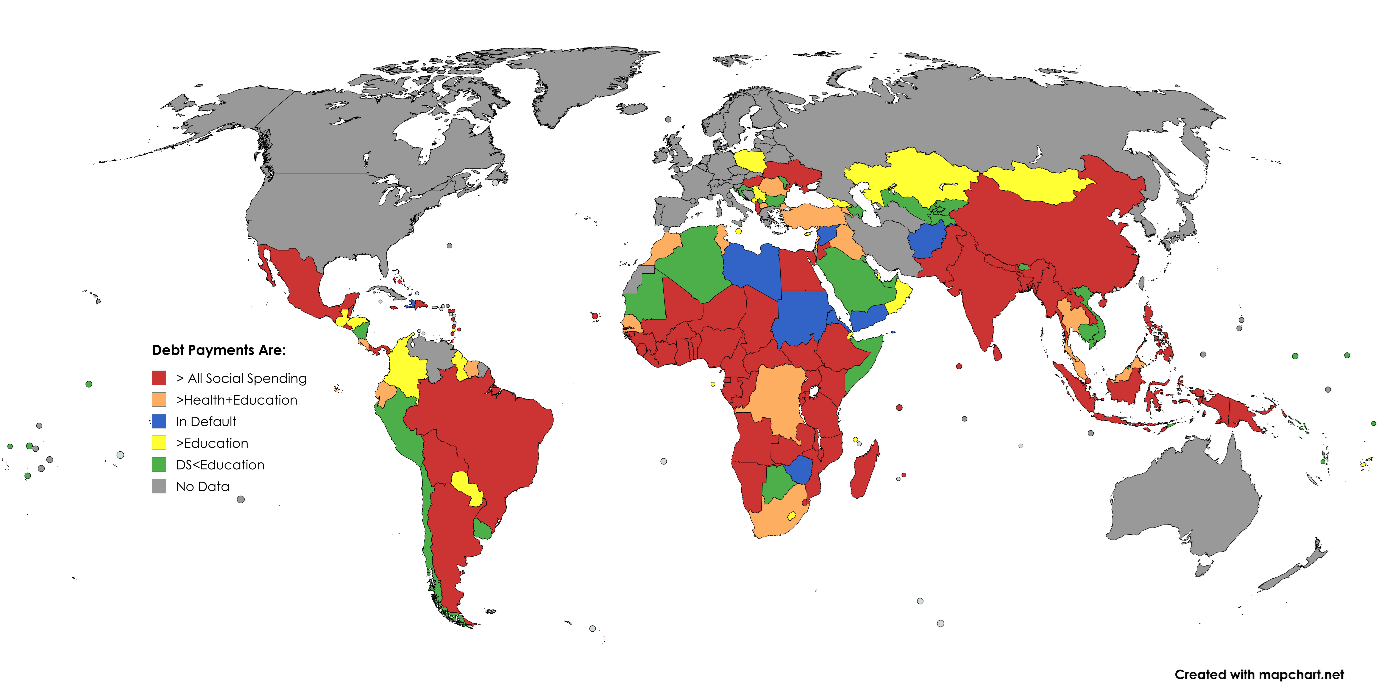

Why is it the worst crisis ever ? With the HIPCs, many of them had been in arrears for many years and so weren’t paying much debt service (except to the IMF and World Bank). But now almost all countries in the global South have astronomical debt payments. At Development Finance International we have built a Debt Service Watch database, the only one which compares external and domestic debt service with core social spending for 2025-26. It shows that on average countries of the global South are paying 35% of their budgets on debt.

As you can see from the map below, in almost all countries, debt payments are higher than education spending. Overall, 5.2 billion people live in countries where debt payments are higher than total social spending. On average, debt service is 3 times education spending, 5 times health spending and 9 times social protection spending. And in almost all of these countries, the high debt payment burdens go on for the next decade.

As a result, increasing numbers of governments - and especially citizens - are shouting much louder about the need for debt cancellation. They are angry because since COVID-19, their governments have been cutting social spending and increasing taxes even faster to make rapidly rising debt payments. We have seen this clearly in the 2024 Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index which we produce with Oxfam, where many governments rolled back anti-inequality policies in 2022-24 (though some countries continue to fight inequality well).

In addition, citizens are basing the demand for debt cancellation on new arguments such as reparations, decolonisation and paying for climate and nature justice (on average debt payments are 98 times higher than what governments are spending on climate !).

On the other hand, two things haven’t changed since the first crisis -though they are often used as excuses by the creditor community to say they make debt relief much harder.

Commercial creditors are more prominent. Banks have mostly been replaced by bondholders and investment funds. Both in their day have acted like the Wild West in terms of overcharging countries. Last time it took “moral suasion”, tax incentives and strong laws to get most creditors to participate in relief. Once again a minority are refusing to provide relief and launching lawsuits against countries (most recently Ethiopia). One of the things I am most proud of is helping in 2010 to design the UK “anti-vulture fund” law which forced recalcitrant creditors to participate. We urgently need an update of that law.

China is more prominent. China has been lending since the 1970s, and at the forefront of debt relief since 1977, providing as much or more than Western countries. It always wants to use its own processes, and not be corralled into action by the G7 or G20. Its lending shot up and became more expensive in the 2010s, and now it wants to be sure that Western commercial creditors and multilateral institutions will deliver their fair share of relief.

What can we do to end the crisis ? It is easy to design solutions which can achieve massive relief at relatively low cost. We need to focus on cancelling or cutting payments due in the next decade (rather than cancelling all the debt which would cost far more), to free up space for governments to spend money on the SDGs. Countries fall into three groups:

40 lower-income countries need major service reduction, bringing down their payments from 35% of spending to 10% over the next 10 years (the HIPC target). As they don’t routinely borrow commercially, this would not negatively affect their “market access”.

25 are regularly hit by natural disasters (earthquakes, hurricanes, pandemics). They need us to move beyond “pausing” their debt payments for a few years which just worsens the problem, to reducing debt payments for 5 years to allow them to recover.

35 (mostly wealthier) countries, like South Africa, constantly borrow on financial markets to fund their budgets: they need comprehensive measures to reduce their borrowing costs.

To spend the proceeds, countries should build Just Green Transition Strategies to fight extreme inequality, climate crisis and nature loss at the same time – and participatory structures to hold them accountable for implementation. If we fund these with debt cancellation (and new money), we can make massive progress on the SDGs and the post-2030 agenda. But none of this is happening now because world leaders aren’t prioritising this crisis. To get them to focus on ending extreme inequality and poverty, and confront the climate and nature crises, a global popular movement is rapidly growing across the world – please join it now!

END.

Author: Matthew Martin, Executive Director, Development Finance International

Matthew discusses these issues in more depth in our latest podcast episode, unpacking how debt, inequality, and political choice intersect — and why things don’t have to stay this way. Listen here👇