For Millennials, socioeconomic class is back.

I was at a birthday party for one of my son Stanley’s friends this weekend, and I got talking to Alicia, one of the of the mums. Alicia is a single mum, who was born in Jamaica and grew up in London and is saving to buy a house. She still needs to raise around £50,000 for the deposit, which she thinks will take her another couple of years. Then she’ll be able to afford a house —not in this area, but outside the city. For reference, people in the poorest 20% in the UK have an annual disposable income of around £16,000. So, £50,000 is a lot of money.

I thought of her on Monday while I was at a brilliant seminar organised by the International Inequalities Institute at LSE, looking at ‘Why wealth inequality matters.’- you can read the report here and what the video of the event here.

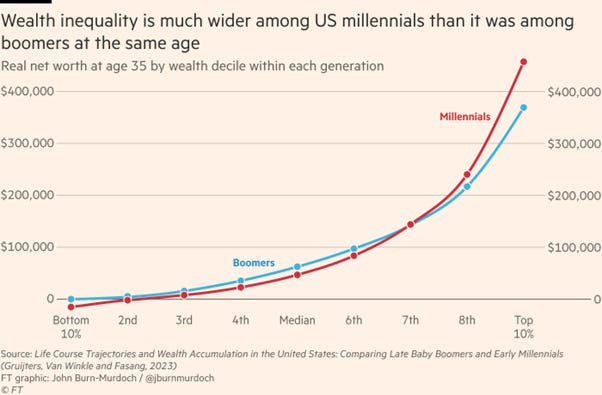

Preliminary findings from research undertaken at the institute presented looked at class and wealth; it compared those born in the 1960s with those born in the 1980s —Baby Boomers and Millennials. For the Boomers, their parents’ socioeconomic class made very little difference as to whether they found themselves in the top 10% or bottom 10% in terms of income when they reached the age of 35-40. Remarkably, 16% of those who came from upper classes (“upper professional and managerial backgrounds” in the official classification; people with parents with jobs like judges, CEOs or doctors) ended up in the bottom 10% of wealth when they reached 35-40. On the other hand, Boomers from the working class (“routine occupational background” in the official classification; people with parents who had jobs like waiter, bus driver, or cleaner) were as likely to be in the top 10% of wealth at age 35-40 as they were to be in the bottom 10%.

For Millennials, there has been a dramatic shift. For this generation, far fewer of those born with parents in upper classes were in the lowest wealth decile at age 35-40. In contrast, far more Millennials with more working-class parents ended up in the poorest 10%, and very few have moved up to the top of the wealth distribution. Basically, this means that in the UK today your chances of acquiring wealth are far more determined by class if you are Millennial than if you are a Boomer.

The paper found that a major explanation for this is housing. As house prices have shot up in recent decades in large parts of the UK, the proportion of young people able to become homeowners has fallen. For the Boomer generation, one of the best indicators of whether you became a homeowner was how much money you earned. For Millennials, the money you earn is not the explanatory factor —instead it’s how much money you have been given to help you buy your house by “the bank of mum and dad.” So much so that 60% of those who come from upper class backgrounds in the UK but are in working class jobs own their own home, compared to just 18% of those who come from working class backgrounds. This perhaps explains, at least in part, the proliferation of baristas, bakers and brewers from the middle classes that have become a ubiquitous feature of gentrified London.

Wealth inequality increased by gender and race

This situation is made worse by gender and racial discrimination; two of the other papers looked at these two interrelated aspects of inequality. The gender wealth gap is really significant in the UK and gets much larger the further up the wealth distribution you get —women at the top of the wealth distribution have 28% less wealth than men.

People from non-White backgrounds also have significantly less wealth, with the average Black Caribbean household like Alicia’s being nearly £100.000 poorer than the average White household.

For someone like Alicia, rapidly rising house prices means that the possibility of home ownership is constantly being pushed further into the distance, in both time and space. All around our area young White couples with babies are buying houses for the best part of a million pounds —oftentimes receiving £150,000 pounds or more from their wealthy parents.

The return of Aristocratic wealth worldwide

The UK is a reflection of a worldwide phenomenon: the return of inheritance as a vital determinant of your life chances. Over the next 25 years, the world is set to become an “inheritocracy,” with over $100 trillion currently being transferred from Boomers to their heirs.

All billionaires under the age of 30 inherited their wealth. Inheritance taxes, cleverly rebranded as “death taxes” by their right-wing opponents, have been repealed or eviscerated. We found that half of the world’s billionaires (46%) are from countries with no inheritance tax on wealth and assets passed to direct descendants. This means that these super-wealthy individuals will be able to pass on a combined fortune of $5 trillion completely tax-free to the next generation, keeping the concentration of wealth in the hands of the same families, and perpetuating inequality. This is more than the entire GDP of Africa.

This intergenerational transfer of wealth is presented by the mainstream media in a typically class blind way, as if every Millennial or every Gen Zer will benefit equally. In fact, this huge transfer of wealth will do what it always does: drive up inequalities of wealth. And as we know, the vast majority of people already do not have any wealth at all, and in fact in many cases have negative wealth.

I don’t think this is just a UK or rich world phenomenon, either. In my experience working on inequality with colleagues from countries all over the world, there is a constant view that socioeconomic mobility is reducing, not increasing. That people getting the good jobs in Malawi, or Peru, or India, are increasingly those from wealthy backgrounds. Take this reflection from my good friend John Makina who was our country director in Malawi:

I think this return of inheritance should worry everyone, across the political spectrum. If history shows us one thing, it is that aristocracy does not work well as a way of governing a country. Governments everywhere need to take strong action to tax inheritance (how about we rebrand it the “Fair Future Tax”?) and prevent excessive concentration of wealth in the first place.

The Boring Bahamas

Two other excellent studies presented on Monday looked in detail at one of the recent reforms in he UK to partially close tax loopholes used by the super-rich where they can legally define themselves as not living in the UK even though they do (the famous “non-doms,” which include the Prime Minister’s billionaire wife).

A constant argument against wealth taxes is that the rich are hypermobile and will simply leave. This study was designed to see whether this actually happened. The findings? There was a small increase in those who left, but the vast majority of the super-rich stayed, despite having to pay around 150% more in tax.

The quantitative study was complemented by some qualitative interviews with the super-rich, whose responses were very entertaining and worth quoting in full:

“If somebody had offered us Hong Kong… It was a fabulous place with young children, but it’s a very artificial society and… Well, I don’t particularly like Dubai. I find it quite authoritarian. It’s pretty hard to get a beer, which is never very attractive from my perspective. Singapore’s all right. I find it a bit sterile. I always describe Singapore as being the sort of place that if Walt Disney had to invent an Asian city, they would invent Singapore.” (Brad, 60s, law)

“Yes, what puts me off it is that I have a nice life here [In London], you know, my clients who moved to the Bahamas were bored to death. Sun, sea and sand. Okay, it’s great for a couple of weeks to charge the batteries but after a while you think, well, I’d quite like to go and watch an opera, well, you can forget that, there’s not a theatre in the Bahamas.” (Luke, 50s, law)

“I have a lot of friends who, you know, they don’t domicile their… and they were like, ‘Oh they're going to change this.’ Or, you know, ‘I'm going to make £5 million less a year.’ And, you know, ‘This place doesn’t deserve me.’ So it’s like you know what? Just fuck off, all right? You know, seriously. You know. If that’s the reason why [you] live here… There's always somebody to replace you.” (Wilfred, 50s, consulting)

END.

Author: Max Lawson, Head of Inequality Policy at Oxfam International and EQUALS podcast co-host. He is also the co-chair of the Global People’s Vaccine Alliance.

Read our latest Bulletin ‘the global land rush for climate action.’

Always remember to share and follow us on X and connect with us on LinkedIn.

good one.