Struggling to find money to vaccinate

It is hard to think of a more popular initiative with donor governments than Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Backed strongly by the Gates Foundation, Gavi has invariably had vocal and significant support from the leaders of the world’s richest countries. Since it was founded in 2000, Gavi has always raised the funding it has asked for. In fact, at its last replenishment, Gavi got a billion dollars more than it requested. This was in April 2020 as the Covid crisis was unfolding, which helped demonstrate to the world the incredible power of vaccines in stopping diseases from spreading, mutating and growing.

Gavi is far from perfect. It is a public private ‘partnership’ that has pharmaceutical corporations on its governing board which creates a huge conflict of interest. Gavi is arguably far too close to private philanthropy and Big Pharma and doesn’t do enough to drive down vaccine prices overall, despite its huge market power. Gavi’s ‘innovative’ model to front load funds to buy vaccines via private bonds has also run into criticism for its net loss of aid in order to pay for high interest rates and shareholder returns. But even its fiercest critics would agree that Gavi has given a huge boost to vaccination rates across the Global South and saved millions upon millions of lives as a result.

So when Gavi fell short last week of its request of $11.9 billion by a massive $2.9 billion, despite all the power and influence of the Gates Foundation and the glitz and glamour of Global Citizen behind it, we should all be very worried indeed.

Oxfam released figures ahead of the G7 last month showing that G7 aid is set to be cut more than ever before – the biggest being the US which also withdrew from Gavi this week. But this is not just a US story. All the major economies are set to scale back on their aid commitments. The UK, once a global leader in giving life-saving aid, is due to cut its aid down 1999 levels.

The UK remained the biggest donor to Gavi, but despite the Foreign Secretary David Lammy saying ‘as others step back, we are stepping forward’ at the Gavi replenishment they actually cut their contribution by 25%. This is all the more concerning given health is supposed to be one of only three development priorities going forward for the UK government. Perhaps this is more accurately described as a case of ‘whilst others leap back, we are only stepping back’.

While these statistics are shocking in themselves, they become much more real when we consider the human impact- for example that of unvaccinated kids dying of easily preventable diseases. A study published last week in the Lancet models 14 million more deaths from 2025-2030 as a result of the USAID cuts alone.

The leaders of the richest nations are making terrible, brutal decisions here.

Always money for war

The Gavi replenishment was held in Brussels during the evening. This was deliberate because the NATO summit was being held up the road in The Hague that same day. The idea was to make it easy for NATO Leaders and Foreign Ministers to jump in the car and go from one to the other.

In the end most leaders skipped the Gavi replenishment even though they usually attend it. But many of their foreign ministers did do both events.

At NATO, European leaders were falling over themselves to commit to dramatic and rapid increases in military spending. All but one of them committed to increase their military spending to 5% of GDP.

They originally set themselves a 2% of GDP target in 2014, giving themselves ten years to get there. By 2025, 23 out of 32 had met this target. Now they are aiming at 5%. That would bring their total spending on the military to $2.7 trillion dollars at today’s GDP levels.

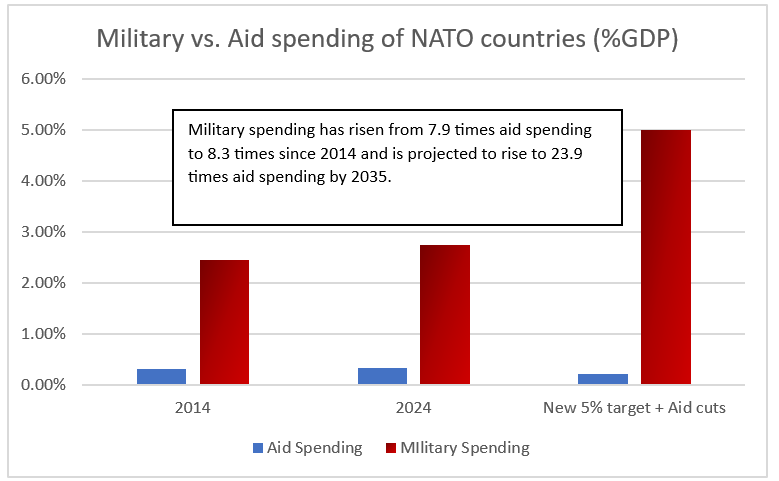

The contrast with development aid could not be starker. Donor countries agreed to a target of just 0.7% of GDP in 1970. Fifty-five years later, only four are now meeting this target. Their total spending on aid is just $179 billion, or 0.33% of the GDP of NATO members.

In 2014, military spending was 7.9 times more than the aid spending of NATO members. By 2024 it had risen to 8.3 times. If they meet their target of 5% of GDP by 2035, and if we factor in aid cuts announced, then military spending will be 23.9 times more than aid spending by 2035.

The only speaker at the Gavi replenishment to speak of the sharp juxtaposition between the two meetings was the Greek Prime Minister, who committed $5 million to Gavi:

‘I was thinking that some of us came back from the NATO Summit in order to make sure that we are with you here today to reconfirm our support to Gavi. I was thinking that if we can afford, and rightly so, I may add, to spend 5% of our GDP on defence over the next years, we certainly can afford to contribute 5 million to Gavi.’

(Great that they increased their contribution from $2 million to $5 million, but to put that in context, 5% of Greek GDP is $12 billion. A single F-35 fighter bomber costs up to $110 million).

A kind of madness

This cartoon is from eighty years ago, showing that this problem – where there is never any issue in finding money for war but every penny for the poor has to be fought for – is a very old one.

Broadly speaking, around half the population in European NATO countries support more military spending, but there is significant variation. But I think it is unlikely that NATO publics support spending a whopping 5% of GDP, especially when they are being told that, as a result, there is no money available for schools or hospitals.

Even those who do not necessarily question the need for increased military spending in principle point out that military spending is about as inefficient and ineffective as it is possible to be, and that more money will simply mean more waste and bigger profits for arms manufacturers.

Arguments that military spending will boost growth and jobs barely stand up to scrutiny either, especially contrasted with other sources of public investment. A new hospital is broadly the cost of ten fighter jets. Think of the jobs, investment and wider ongoing benefit to society of a new hospital in contrast to those ten aeroplanes.

Of course, it is also a false choice, in that if we taxed the richest people fairly, arguably NATO countries would be able to increase spending on public services and lifesaving aid as well as spending more on the military.

But for me though, even if new revenue was found by taxing the super-rich, I don’t think spending 5% of GDP on the military is either justified or necessary. In fact, it seems likely to me that a new arms race would not only waste huge amounts of money but perhaps actually increase the threat of conflict and violence, rather than reduce it, with the main beneficiaries being arms manufacturers and their rich shareholders.

Given the huge needs of humanity, not least the most existential threat of climate breakdown, to be squandering our vital resources on bullets and bombs rather than classrooms and clinics feels to me a kind of madness.

(Thanks to Didier, Salva and Anthony for help with this blog.)

ENDS.

Author: Max Lawson, Head of Inequality Policy at Oxfam International and EQUALS podcast co-host. He is also a visiting Professor in Practice at the LSE International Inequalities Institute and the co-chair of the Global People’s Medicines Alliance.

Listen to our latest episode featuring Nick Shaxson on how monopoly power is shaping inequality.

Always remember to share and follow us on X and on LinkedIn.