Negotiation November and Kenya’s inequality crisis

Amid a whirlwind of bilateralism, Oxfam Kenya’s latest report is shining a light on the country's inequality crisis.

November was a hive of activity in the fight against inequality.

In the space of a few weeks, we’ve had:

COP30, where the President of Brazil, Lula da Silva, quoted Oxfam’s research, putting climate inequality on the centre stage. Ultimately, the conference ended in more heartbreak than hope. Read last week’s bulletin on Oxfam’s report if you missed it.

The G20 hosted by South Africa, where the President of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, put the inequality crisis firmly on the agenda. The final communique was watered down, with countries clearly spooked by the ghost of President Trump. More on this below.

The World Social Summit (WSSD) in Doha, Qatar, where the Doha Political Declaration was adopted, centring social development on poverty eradication, full and productive employment and decent work for all, and social inclusion.

The UN tax convention in Nairobi continued negotiations for the first UN tax convention.

What have we missed? Comment below!

Oxfam’s ‘big heads’ might have been getting quite a lot of use recently, but it does feel like all these negotiations are happening over each other, rather than with each other.

In this week’s Bulletin, we start with a look at what happened at the G20, then put a spotlight on a new Oxfam report on Kenya’s inequality crisis.

G20

Standing up to bullies. President Ramaphosa and the South African government set an example to the world in ensuring the G20 stood firm and collectively agreed on a leader’s declaration – defending multilateralism – despite U.S. strong-arming.

Rich countries and their allies did water down the communique, clearly spooked by the ghost of President Trump. The communique does not reflect the clear momentum worldwide for taxing the super-rich established during the Brazilian G20 presidency in 2024. Nevertheless, the agreement was a clear victory for South Africa and for multilateralism

History made on inequality. This was the first ever meeting of world leaders where the inequality emergency was put at the centre of the agenda. This too is a testament to South Africa’s leadership – one that put the billions before the billionaires. Arguably, the biggest legacy of the South African G20 could be the beginning of the road for the creation of a new International Panel on Inequality- an Inequality IPCC- with the leaders of Norway, Spain, Brazil and South Africa all signalling their support together with the European Council and the AU.

Kenya’s inequality crisis

Extreme poverty in the face of economic growth. Since 2015, an additional seven million Kenyans have fallen into extreme poverty, an increase of 37%. Severe and moderate food insecurity rose by 17 million between 2014 and 2024, an increase of 71%. The cost of food is 50% higher than it was in 2020.

This has been accompanied, however, by a decade of 5% per year real-term economic growth (excluding 2020).

Growth for the rich. The richest 125 Kenyans hold more wealth than 77% of the population, equivalent to 42.6 million people. The richest 1% own 78% of Kenya’s total financial wealth. This clearly shows that without redistribution, growth alone will continue to enrich the richest while deepening poverty for the majority.

Women are hit hardest. Women earn just KSh 65 for every KSh 100 earned by men, and are five times more likely to engage in unpaid care work, and face significant barriers in land ownership. Only 13% of women hold legal rights to agricultural land, dropping to 4% among women in the poorest households. Asset ownership in male-headed households is three times higher than in female-headed households.

Inequality in public services. Education, health and social protection structures are chronically underfunded.

Children from the poorest 20% of households receive almost five fewer years of schooling than those from the richest 20%. When adjusted for inflation, the amount of money per pupil that the government spends on primary schools is equivalent to just 18% of what it was worth in 2003.

The Social Health Insurance Fund is unaffordable for many and has benefited private healthcare providers the most. In 2022, only 20% of National Health Insurance money went to public health facilities.

Only 9% of Kenyans are covered by at least one form of social protection. Among the poorest, only a fifth receive social assistance.

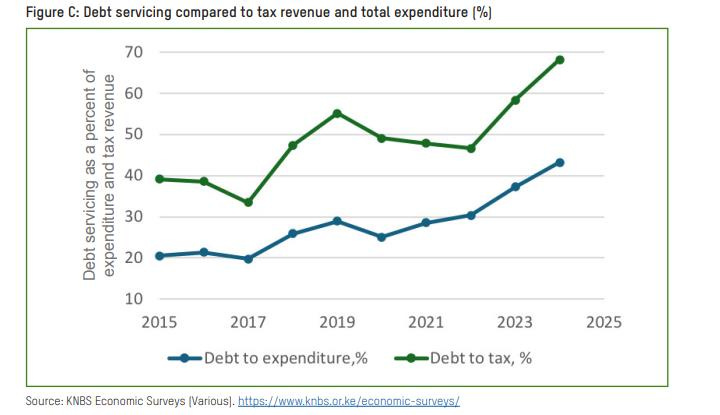

Debt repayments over social spending. In 2024, out of every 100 shillings collected in taxes, 68 shillings were used to repay debt. This is double the amount in 2017. Debt repayment is twice the education budget and nearly 15 times the national health budget.

Taxing the poor. Kenya’s tax system is over-reliant on regressive VAT/sales taxes, which means that people who spend nearly all their income on basic items are paying more in taxes, as a share of their income, than their wealthier counterparts. In 2023, the government introduced new flat-rate taxes on housing and health, which mainly affected low-income earners, and gave property owners some breathing space by reducing the tax rate on rental income by 2.5 percentage points.

Inequality protests. IMF-imposed austerity measures, such as tax hikes that affect people on lower incomes and government budget cuts, are further widening the gap between the rich and the rest. Inequality was at the heart of the nationwide protests in June 2024.

The colonial legacy. Today, neo-colonial systems of domination reproduce colonial injustices. The dominance of the IMF in shaping the country’s economic policy, exploitative practices, including on trade and tax avoidance by Multinational Corporations, and the dominance of debtor interest in the global financial architecture continue to shape inequality in Kenya.

Something to read/listen to/watch

Read Oxfam’s Rune Møller Stahl’s ‘In Denmark, Social Democracy Is Failing’

Listen to the Equals podcast with Anna Marriott and Dr. Aquina Thulare on healthcare financialization and the fight for universal health.

And in lighter news, ‘How one man accidentally became the richest man of all time, a multi-quadrillionaire!’