Some wonderful progress in saving children’s lives

I lived in Malawi from 1999 to 2002. At that moment, the turn of the millennium, in the poorest Malawian families 191 children out of every thousand born would die before the age of five. This means in poor families (those in the bottom 20%) approximately one in five newborn babies was not reaching their fifth birthday.

As of 2022 that figure is now 47, so instead of one in five, the figure is now one in 20 babies born into a poor family in Malawi is likely to die by the age of five. That is still an appallingly high number. In the UK it is 4.7 in the poorest areas of the UK. That is one chance in 212. But it is also an enormous improvement in a little over twenty years. An improvement that is all the more impressive because there were 11 million Malawians in 2000 and today there are 22 million. That is a lot of births.

More healthy, and more equal too

But there is another aspect to this graph which is heartening and repeated in many countries; not only are the average number of children dying, the gap between the rich and the poor is too. When I lived there, the life chances of a child from a rich family were much higher than those from a poor family. Today the gap has closed dramatically, and with this the health inequality.

This process, of greater progress overall, but also a greater increase in health equality, is far from guaranteed.

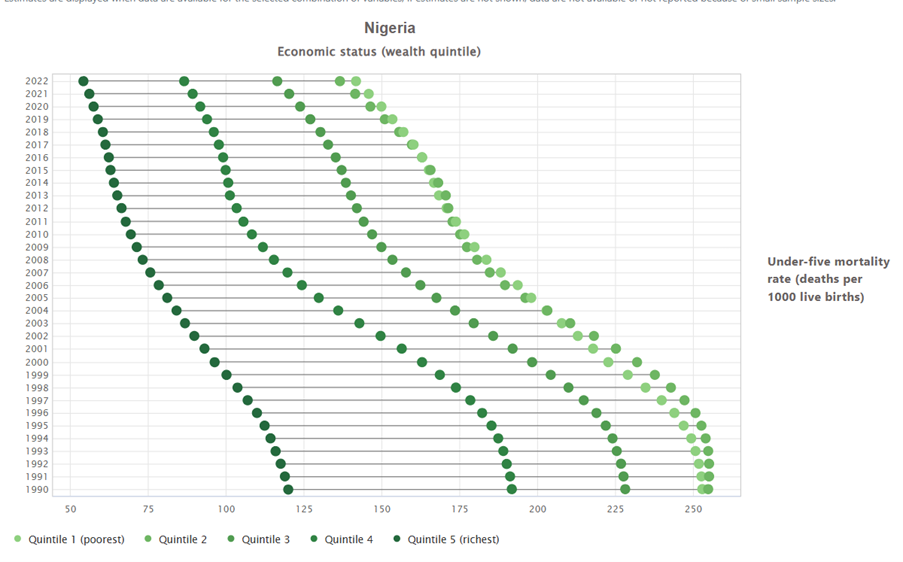

Progress that is not guaranteed

Take Nigeria for example. Again since 2000 a big improvement- average under five mortality has reduced by a little over a third since 2000, from an average of 180 per thousand live births, to 110 in 2022. Yet you can see that there has been minimal decrease in health inequalities; a child in a poor family is twice as likely to die before they are five years old than a child in a richer family.

In the year 2000 Malawi’s per capita income was $121 dollars a year. In 2022 this had risen to $563 a year; Malawi remains one of the very poorest countries in the world. The per capita income of Nigerians is more than three times higher than Malawians ($1663) but a Nigerian poor child’s chance of dying before they are five years old is three times higher than a Malawian child.

Simple ways to save a life

What does this show? For one thing progress in health outcomes can be achieved rapidly even in some of the poorest countries in earth, but that also average improvements can mask huge differentials in the level of health equality. Simple policy steps can make a huge difference- in Malawi mosquito nets cost money when I lived there and were not common. Yet since the mid 2012 they have been available free and widely distributed- that alone makes a huge difference.

Health equality, economic inequality

During this period economic inequality in Malawi grew really quite sharply too, Malawi reached a high of a Gini of 0.45 in 2010 (the World Bank threshold for high inequality is 0.4). It has since fallen back down a bit, but nevertheless, you saw a big increase in health equality whilst they had a big increase in economic inequality.

To my mind there is no doubt that high economic inequality is a bad thing for lots of reasons, and governments should do far more to reduce it. GINI should matter at least as much as GDP. But if other inequalities, like those in health and education, can be significantly lower, this does make a big difference to people’s lives even if economic inequality remains high.

A lot of this in turn is about policies; if education and healthcare are free and universally available, then disparities of income matter less. When they are instead commodified, and privatised for profit, then how educated your children are, or whether they live to the age of five or are killed by malaria before then, depends on how much money you have. In such cases disparities of income matter a lot more.

As a concerning footnote- so much of the data disaggregated by wealth quintile for health and education comes from Demographic and Health Surveys that have been running since 1984. They were funded by USAID and that funding was ended earlier this year, and now their future is uncertain. Given all the other immediate needs cut short by the cuts to USAID this cut to research can feel perhaps not as important, but I think that is a huge mistake- this data is invaluable. Some donors have come up with emergency funding which is great and I hope it gets fully funded again soon.

Author: Max Lawson, Head of Inequality Policy at Oxfam International and EQUALS podcast co-host. He is also a visiting Professor in Practice at the LSE International Inequalities Institute and the co-chair of the Global People’s Medicines Alliance.

Listen to the latest EQUALS episode featuring Ingrid Robeyns on having a wealth cap.

How Much Wealth Is Too Much? Ingrid Robeyns on the Case for Limitarianism.

Can a society survive when a few own everything?

Always remember to share and follow us on X and on LinkedIn.