During the fight against apartheid, as a student organiser, Cyril Ramaphosa was imprisoned three times. Aged 22 he was held in solitary confinement for 12 months. I can’t imagine what solitary confinement for 12 months would feel like, at such a young age, how it would impact you, or how strong you would need to be to cope with this. He was imprisoned again aged 24 for a further six months, and then finally in 1976 following the huge student uprising in Soweto (his birthplace) for another six months.

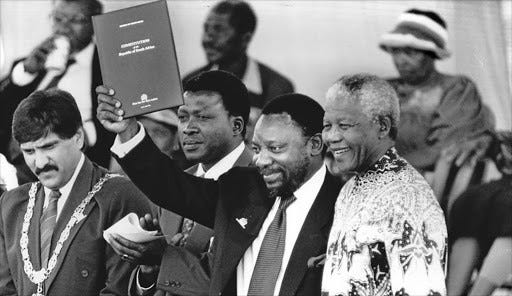

He rose to become the head of the National Union of Mineworkers and played a leading role in the fight against Apartheid. During the transition to democracy, he was the close confidant of Mandela and led the negotiations with the white government.

He also led the process to develop South Africa’s new constitution.

The heroic struggle against the white supremacy of the Apartheid government was a big thing as I was growing up. The pitched battles fought on the township streets between the armoured police and the young people regularly on the nightly news. Joining my parents on anti-Apartheid marches, drinking tea from a ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ mug and listening to the fantastic song of the same name. South Africa was also the first place I lived and worked in Africa, twice in the 1990’s. It is a truly incredible country, which has a huge place in my heart.

I think it is so critical we remember this incredible struggle against Apartheid, which was the last of many other successful struggles across the continent for national liberation. Struggles that so many people died for. We should ensure our children know these stories. Sadly, in today’s world I fear that many young men, if asked who was the most famous South African, would be more likely to name Elon Musk than Nelson Mandela.

SA and the USA

The US, under Ronald Reagan, was one of the last countries to end its support for the white minority government in South Africa. The UK, under Mrs Thatcher was one of the others. Theirs was a policy of ‘constructive engagement’. This policy was promoted as an alternative to the economic sanctions and divestment from South Africa that congress, the UN General Assembly and the global anti-apartheid movement were all calling for.

Recently the relationship between the USA and SA has been back in the news, with President Donald Trump repeatedly falsely accusing South Africa’s government of allowing for violence against white farmers and expropriating their land. He has offered asylum to white farmers seeking to flee the country. Trump has given enormous weight to these false allegations and theories, theories which Ramaphosa himself said this week, ‘conveniently align with wider notions of white supremacy.’

An unlikely radical

Despite his role in the struggle, Cyril Ramaphosa is nevertheless a bit of an unlikely radical. For a start he is one of Africa’s richest men, worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Mandela had wanted him to be his successor, but the ANC decided otherwise, and Thabo Mbeki became president. At that point Ramaphosa left politics and moved into the private sector and made a huge amount of money.

He has also not really done much as President to challenge the underlying neoliberal economic policies that have been in place in South Africa since the late 1990’s and have underpinned its extremely high inequality. The National Minimum Wage reform, that he personally pushed for, was mainly done when he was Deputy President, so his actual term as President of the ANC and of the country has been disappointing for those who thought he would use his office to advance a more radical, pro-poor agenda.

But nevertheless, looking back over the last five years, globally at least he is one of a handful of leaders who are bravely taking on the powerful and fighting for the side of good. It began with his very vocal advocacy around what he described as ‘vaccine apartheid’; when South Africa and India fought at the WTO for the right to manufacture generic Covid-19 vaccines. The restriction of vaccines to the rich world to protect pharmaceutical patents and exorbitant monopoly profits cost millions of lives and remains to my mind one of the greatest crimes committed so far in this century. Ramaphosa was firmly on the right side of that battle.

Then in 2023, South Africa led the world by bringing the case to the International Court of Justice accusing Israel of committing genocide in Gaza. I remember going a march in London around that time and seeing the sudden flood of South African flags flying next to the Palestinian ones and how amazing that was. Mandela famously said, ‘We know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians’ and Ramaphosa’s government clearly took this to heart in taking this incredibly brave step in support of Palestine.

Finally, this year with the G20, Ramaphosa has shown both steel and dignity in standing up to geopolitical bullying. Though President Trump refused to attend the G20 – which was held last month in Johannesburg, chaired by South Africa, and the first G20 in Africa– the U.S. publicly warned South Africa not to agree a communique at the meeting. In the run up to the summit, many diplomats in the G7 were saying the likelihood of a communique was very low, that South Africa should make do with a ‘chair’s statement’ as has happened at the G7.

But the South Africans stood firm, and a communique was agreed. Whilst the communique was watered down in key respects as other nations like Argentina – an ally of the Trump administration – lobbied hard within the negotiations, it was nevertheless a major achievement that it was agreed at all. At the summit itself Ramaphosa showed his experience as a canny negotiator by declaring the declaration agreed and passed in the first session of the summit, before any others had time to block it. As we said in our reaction, ‘South Africa has set an example to the world in ensuring the G20 stood firm and collectively agreed on a leader’s declaration – defending multilateralism – despite U.S. strong-arming.’

Not only this, but Ramaphosa also personally chose to commission, as part of his G20 presidency, the first ever report to the G20 on the global inequality crisis, written by the Extraordinary Committee chaired by Joseph Stiglitz. They also came out fully in support of the main recommendation of the committee, the establishment of an International Panel on Inequality, a kind of ‘Inequality IPCC’, and rallied the leaders of Brazil and Spain to support them in this. If this panel is actually formed in 2026, and I really hope it is, it will be a tremendous legacy of the South African G20.

No invite to Miami

The G20 presidency rotates, and now has passed to the USA, who were quick to say that South Africa is not invited. Last week there was an extraordinary exchange on substack between the US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and South African Foreign Minister Lamola, which will be something captured in the history books. Lamola’s final words are worth quoting in full:

‘Secretary Rubio, the world is watching. It is growing weary of double standards. It is tired of lectures on democracy from those who seem to have forgotten that democracy, at its best, must listen as much as it speaks.

We do not seek your approval for our path. Our path is our own, chosen by our people and guided by our sovereign laws. But we do seek, and we will always extend, a hand of respectful partnership.

We believe in a world where nations can disagree yet still find common ground for the sake of a child’s health, a community’s stability, and our planet’s future. That is the world Madiba fought for. That is the world we, in South Africa, are still building every single day.’

This is what standing up to geopolitical bullying looks like. It now remains to be seen whether the other nations of the G20, and especially the G7, will stand with South Africa, and demand their inclusion at the G20. I suspect many of them will not fail to disappoint, but I do hope that some at least take heart from the bravery of the government of Cyril Ramaphosa.

ENDS.

Author: Max Lawson, Head of Inequality Policy at Oxfam International and EQUALS podcast co-host. He is also a visiting Professor in Practice at the LSE International Inequalities Institute and the co-chair of the Global People’s Medicines Alliance.

This analysis of Ramaphosa as an 'unlikely radical' really captures something important. The tension between his private sector wealth and his willingness to challenge global power dynamics at the G20 and ICJ is fascinating. I've seen firsthand how quickly countries with less historical moral authority get isolated when they push back on inequitable systems, so the way he leveraged SA's anti-apartheid legacy was pretty shrewd diplomatically. That said, dunno if his domestic economic record wil create the political capital for this kind of international stance long-term.