How much should we tax billionaires?

Last week saw exciting developments around the Brazilian government’s proposition that the G20 (which they are chairing this year) should tax the super-rich. The Brazilians have asked the brilliant Gabriel Zucman to come up with a proposal for the G20 on how this can be done. Zucman is proposing the G20 work together to make sure billionaires pay taxes that add up to at least 2% of their wealth. The idea is to mirror the deal done at the G20 recently to establish a global minimum tax of 15% on corporations.

The Zucman proposal, although reported as a wealth tax, is actually more sophisticated. The proposal is that all of the taxes on rich individuals, which can be combination of income or wealth taxes, should not add up each year to less than 2% of their total wealth.

This is clever, as it leaves national governments in charge of how they actually tax the super-rich. It would accommodate, for example, Joe Biden’s proposed billionaire income tax of 25%. Countries can choose what mix of income and wealth taxes they implement, as long as their super-rich pay taxes that equate to at least 2%.

I never liked the idea of a minimum tax, which is a clever reframing of the debate that emerged out of the corporate tax discussions at the OECD. The problem is the floor is at risk of rapidly also becoming the ceiling, as all countries converge on the minimum. Certainly, I think as campaigners we should never stop calling for what is needed, rather than minimums. After all, it wasn’t that long ago that top rates of tax were 90% or more, and corporates paid 50%.

Stopping smoking and deterring new smokers

So how much tax should billionaires pay? Like any tax, it depends on whether the tax is designed to raise revenue or shift our economy and the way people behave. Do we tax cigarettes to raise money or to stop people smoking? Is a super-rich tax designed to raise more revenue from the richest people in the world? Or is it designed to reduce the number and wealth of billionaires, and in so doing reduce the levels of extreme inequality that are so detrimental to our common life in so many ways?

Also, is the tax high enough to not only stop smoking but deter new smokers? High enough that it structurally shifts the economy to deter people from securing huge concentrations of wealth? This was the aim of the extremely high income taxes, in the US and UK in particular, up until the 1980s. Their aim was not to raise money, but to keep wages compressed. What is the point in asking for a pay rise if 95% is going to be taken in taxes? These taxes appeared to work. Certainly, as soon as they were removed we saw the relentless rise in CEO pay —a typical CEO now gets paid hundreds of times more than the average worker.

To design such a tax, the first thing to establish is how fast billionaire wealth is growing on average. Over the last decade, billionaire wealth has grown at an average of 6.8% a year. Since 2020, this has accelerated to 11.6% a year.

Money makes money.

Why is it that rich people can get such consistently high returns? In “Capital in the 21st Century” Piketty looks into this in a very clever way. Data for billionaire investment strategies is not available so he looked at US universities instead. He looks at university endowment funds in the US, where data is publicly available, and finds that the bigger the endowment fund, the more it can invest in top investment and fund managers, and in so doing get the biggest return. Whilst the average was 8%, for universities with less than $100 million the figure was 6.2%. For Harvard and Princeton, which have huge pots of money to invest, the return was 10.2%, a full 4% higher. Piketty found that these higher returns were because they have more money invested in complex, diversified investments, like private equity, hedge funds and derivatives. This requires highly skilled management. Harvard spends $100 million a year on investment managers.

Equally billionaires can afford to spend a lot of money ensuring their money works as hard as possible for them, guaranteeing above average returns year in, year out.

They can afford to pay the accountants and lawyers and wealth managers that hide their fortunes away from revenue agencies. One famous study (yet again by Zucman, this time with Annette Alstadsæter and Niels Johannesen) found that the richer a person is, the more tax they avoid.

What levels of tax would therefore be needed to reduce inequality and not just raise money? Oxfam looked at this for our 2023 Davos report, “Survival of the Richest.” Over the last decade, the numbers of billionaires and total billionaire wealth have doubled. I often say that I am glad that as the inequality guy at Oxfam my pay is not performance related. If it was, I would have been sacked some time ago.

Taxes high enough to stop smoking.

In order to keep billionaires’ wealth constant over the last two decades, we would have needed a rate of more than 8% across all countries. To keep their wealth constant between 2016 and 2021, we would have needed an annual rate of 12.8%. Today, if we want to go back to the billionaire wealth levels of 2012, we will need an annual rate of 17.8% from now until 2030. (all these figures from Survival of the Richest).

This is clearly a policy choice. Do we let billionaire fortunes rise remorselessly, or act to reduce them? If we had a goal of ‘ending extreme wealth by 2030’, to mirror UN goals to end extreme poverty, what would it require?

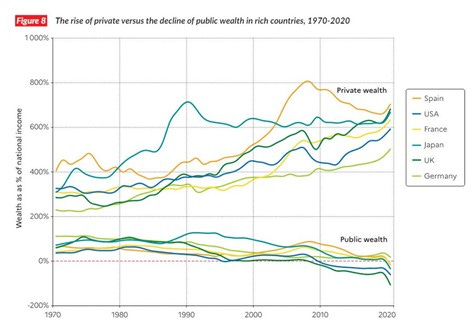

Reclaiming the public trillions

Of course, revenue raising is still a critically important aim of taxing the super-rich. Recent decades have seen a dramatic rise in private wealth and at the same time a reduction in public wealth. The huge injections of money made by governments and central banks into the economy after the financial crisis and during Covid made a major contribution to this. They drove up asset prices, and especially financial assets; and we know that the owners of financial assets are always amongst the richest in society.

I think this is basically public money and should not be in private hands- it is not because these billionaires worked twice as hard or were twice as clever; it is the structural result of the macroeconomic and policy choices of governments. This money needs to be urgently be clawed back and put to good use in ending poverty and stopping climate change. Oxfam calculates that a wealth tax of up to 5 percent on OECD donor countries’ multi-millionaires and billionaires could raise $1.23 trillion a year. This is equivalent to roughly three times the 0.7 percent ODA/GNI target. That is the kind of money we need urgently to fight poverty domestically and across the world, to stop using carbon fast, and to protect and support those already being harmed by climate breakdown.

No longer if but when, and by how much.

Perhaps the most exciting outcome of the last week is that hopefully, finally, we are moving from ‘should we tax the rich’ to ‘when should we tax the rich and by how much?’ instead. This is long overdue. We know that getting the rich to pay more tax is wildly popular across the G20, even with millionaires. It is time G20 leaders started listening.

END

Author: Max Lawson, Head of Inequality Policy at Oxfam International and EQUALS podcast co-host. He is also the co-chair of the Global People’s Vaccine Alliance.

Read our latest bulletin ‘The Great Aid Heist’ here.

Always remember to share and follow us on X and connect with us on LinkedIn.