The disaster divide: the numbers behind the inequality of climate change

How much carbon budget do you have left? In this week’s Equals Bulletin, we look at inequality and climate change.

We’re told that disasters don’t discriminate. Pandemics, floods or earthquakes are equally deadly regardless of if you’re rich or poor. But the truth is that inequality kills, contributing to the death of at least one person every four seconds.

The death toll from COVID-19 was 4 times higher in poorer countries as big pharma made $1,000 a second in vaccine profit, pricing out all but the richest countries. Analysis by The Economist recently found that poorer neighbourhoods in Turkey suffered 3.5 times more damage from last month’s devastating earthquake than richer ones.

When disaster strikes, the less you have, the more you suffer.

In this week’s Equals Bulletin, we’re looking at the looming disaster of climate change and why inequality matters.

Climate inequality in numbers

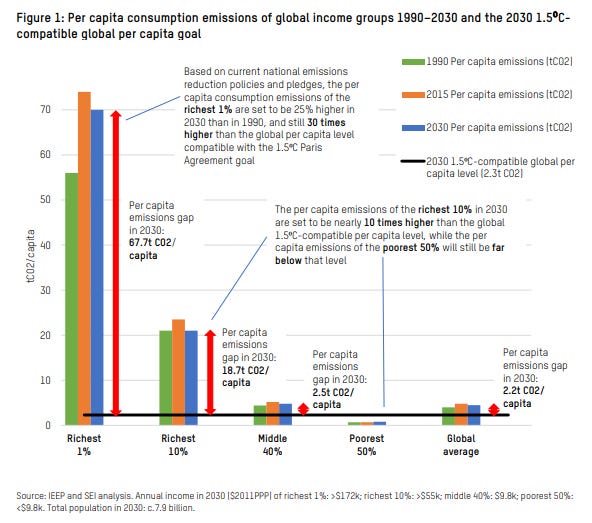

Remaining carbon budget. In 2030 the global carbon budget, the amount of CO2 that can be emitted without tipping us over the 1.5°C red line is about 17Gt of CO2. Divide that equally among the global population and it’s about 2.2-tonnes per person (these calculations are a bit out of date and experts we’ve spoken to reckon it’s now more like 1.8-tonnes, about the same as a round-trip flight from London to New York ).

(Photo via Greenpeace. Activists ground private jet for 6.5 hours in Amsterdam.)

Fair share of emissions? It’s fairly well known that the richest are burning up way more of this scarce carbon budget than ordinary people. But looking at 2030 projections, the extent might still shock you. If you earn more than US$ 172k a year (top 1%) then less than 12 days into the new year you will have used up your entire 2.2-tonne annual carbon budget – not that this will stop you from keeping on going. If you’re in the top 10% (about US$ 55k per year), the same carbon budget will last slightly over a month. On the other hand, if you’re in the poorest half of humanity, earning less than US$ 9.8k, on average you will emit less than half of your carbon budget in the entire year.

Carbon budgeting should not be equal. The 2.2-tonne budget relies on sharing the remaining carbon budget equally. But shouldn’t the people who can afford to both reduce their emissions the most and have the capacity to respond to the inevitable weather-related disasters have a smaller budget? After all, they are most responsible for causing the climate crisis. And shouldn’t those who need the remaining carbon budget to secure a decent standard of living get more? Lifting half the world out of poverty (above $5.50 PPP) would increase carbon emissions by just 18%, broadly comparable to the emissions consumed by the top 1%.

The rich can reduce their emissions easier and faster. It’s not just the greater ability to switch to renewable energy or reduce luxury emissions that make it easier for the rich to cut their carbon footprint. Easily overlooked, a significant proportion of emissions of the richest comes from their investment portfolio. Last year Oxfam found that billionaire investment portfolios were skewed towards highly polluting industries, and if they simply moved their investments to greener funds, they could reduce their emissions by 400%. No wonder some have said that the greenest tax is a wealth tax!

Inequality of harm. Inequality of emissions and the inequality of climate harm are two sides of the same coin. The brilliant new Climate and Inequality Report by Lucas Chancel and the team at the World Inequality Lab produced this chart showing how the capacity to respond (wealth) and emissions are skewed towards the rich. Losses are hugely skewed toward the poorest. The poorest countries are set to suffer the highest losses from climate breakdown, as the map below forecasting changes in GDP shows.

National inequalities. The effect of climate change is deeply unequal at national as well as global levels. Take hunger, for example. The poorest in Sub-Saharan Africa spend 60% of their income on food while the richest spend about 10%. Or heat stress, the average temperature difference between formal and informal housing in India was found to be 7.6°C. A 50°C day in a tin shack crammed into a crowded Delhi slum is a world away from the same day experienced in a spacious air-conditioned house in the suburbs. This is true in the rich world too; findings from Germany show poor people were much more likely to die because of extreme temperatures.

Gender inequality. Women are almost certainly more likely to die in disasters and be more affected by climate change, but there’s little research about it. The figure most commonly cited that women and children are 14 times more likely than men to die in a disaster is from 2007 (and the URL linking to the report is dead) and it’s not hard to see why the data is so sparse. The Emergency Event Database which estimates that over 10k people died from disasters in 2021 fails to disaggregate by gender, income or race. Comment below if you know good research on the topic.

Disastrously unequal. People in poverty struggle to prove their losses after a disaster as their assets are often unregistered and not recognized, while the rich have registered and insured assets, diversified wealth, and better housing on safer land. In Nepal, only 6% of the poorest people got government help following extreme weather events, compared to 90% of the well-off. A paper released last week projected that climate change will increase inequality within every country in the world.

Who pays the bill? At the moment it’s the poorest. Rural families in Bangladesh, for example, are estimated to be spending almost $2 billion per year to repair climate damage or try to prevent it. Finance to mitigate and adapt to climate change is also mainly coming in the form of debt. Loans are dominating over 70% ($48.6 billion) of public climate finance, adding to the debt crisis across developing countries.

Some hope

Pretty depressing right? Here’s some hope to fill your boots. Over 100 countries have backed Vanuatu’s attempt to make it easier to hold governments to account for the climate crisis.

BNP Paribas gets sued. Campaigners in France are suing the bank for funding fossil fuel expansion.

Something to read, watch and listen

Read, the reports that this bulletin draws heavily on, Carbon Inequality in 2030 and Confronting carbon inequality by Oxfam and the World Inequality Lab’s Climate Inequality report.

Watch, these hilarious street interviews to see what people think about carbon inequality.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Listen, to our new favourite podcast discovery, InequaliTalks, the episode on persistent inequality in China is fascinating.

Did you enjoy this week’s Equals Bulletin? Let us know in the comments below and share with friends.