Every day I take my dog, Marx, for a walk in our local park and around the sports fields behind it. Large lime trees, planted a century ago by far-sighed Victorians, tower above you forming a sort of natural cathedral in places. It is not a big park, but it has green space and a playground for the children.

It is well used by local people. On a Sunday evening a group of men from Afghanistan play volleyball whilst Romanian families picnic. Teenagers flirt and smoke marijuana. After school each day the playground is awash with hundreds of local children climbing, swinging and jumping whilst parents sit around and chat. At the weekend there are often birthday parties.

The park is free and open to all. It is a place anyone can visit and is a place where people of all backgrounds and classes can meet each other. On a sunny day it is wonderful to see all the different people having fun and relaxing, and even on a rainy day (this is the UK after all) there are lots of dog walkers and joggers braving the inclement weather.

There are many things that I have noticed being back in the UK after living in Kenya these past few years, but perhaps the thing that has struck me most is the scale of the public sphere. Public parks, public swimming pools, public libraries, public sports grounds, public streets, public transport and of course public education and public health.

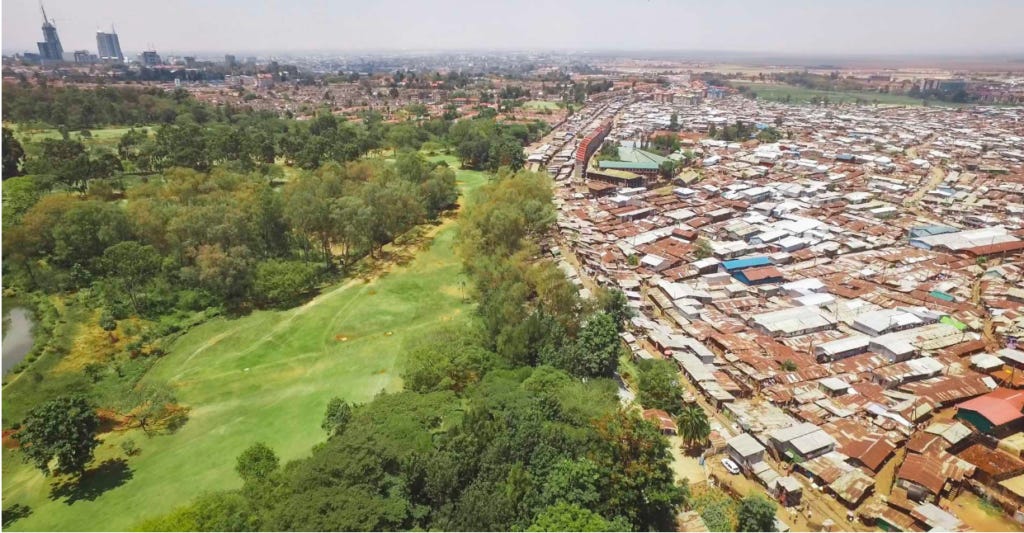

These are all things that many British people largely take for granted. Yet in Kenya such public spaces are in short supply. Nairobi to the casual observer can appear a very green city indeed, but most of this amazing greenery is on private land and in rich areas. There are a few lovely public parks and forests, but not many, and most charge a fee to enter. There is virtually no green space in the large informal slums where most ordinary people live. They are deserts of mud and tin with few trees. The only playgrounds are generally attached to restaurants. Sports facilities are largely at private clubs. Instead of shopping streets there are private malls. There are very few pavements at all. The wealthy and middle classes live in private, gated streets. There is little public transport; the rich drive whilst ordinary Kenyans either walk or get a battered, crowded private minibus if they have money.

Public education and health do exist, but as in so many countries they are poorly resourced. This means they are largely unused by anyone with money, who send their kids to private school and use private healthcare.

In the many malls rich people do mingle, but only with each other. The gated streets can also be very sociable, with kids from all houses playing together, but again they are all from similar social backgrounds. There are very few places at all in Kenya where people from different classes can meet as equals, and that I think in turn has an impact on people’s perception and acceptance of very high levels of inequality as normal.

Of course, the UK is not perfect; far from it. The unaffordability of housing and unavailability of social housing, especially here in London means that the houses near to green spaces become too expensive for those on low incomes. The same is true for schools. Our buses were privatised in the eighties, which has had a devastating impact on poor people, especially in rural areas. Britain has lost 800 public libraries since 2010. There is a constant drive to reduce the public sphere ever more, and brilliant national and local campaign groups fighting back. But nevertheless, the scale of public space is still significant, and it is a wonderful thing.

Public spaces like parks and streets are powerful symbols of equality. They are available for use by everyone, regardless of income. They are a space where rich and poor can meet as equals and get to know each other. They send a clear message that even though you may be richer than me, I am as entitled to this space as you; here your money does not matter. They are also a daily reminder of the power of the public sphere and of collective action. They are a modern-day commons in some ways, and like common land are a constant reminder that there are other, fairer ways of organising human life. And like the common land throughout history they are deeply subversive and therefore are under relentless attack and enclosure.

Michael Sandel, in his book ‘What money can’t buy’ which is one of my favourites, made this point which really struck a chord with me, ‘If the only advantage of affluence were the ability to buy yachts, sports cars, and fancy vacations, inequalities of income and wealth would not matter very much. But as money comes to buy more and more - political influence, good medical care, a home in a safe neighbourhood, access to elite schools… - the distribution of income and wealth looms larger and larger. Where all good things are bought and sold, having money makes all the difference in the world.’

A core principle of neoliberalism is the need to expand the market mechanism into as many spheres of human activity as possible. To commodify as much of human existence as we can. We can often find ourselves falling into this trap; for example saying that unpaid care work should be included in GDP calculations, and should be given a price. In a world ruled by neoliberal economics it sometimes feels the only way to make people take something seriously is to measure its worth in dollar terms.

It is an obvious conclusion but a powerful one; the more of life is for sale, the more how much money you have matters.

Jason Hickel in his brilliant more recent book ‘Less is More’ builds on this from the perspective of the need to prevent climate breakdown and environmental destruction. In so doing he brings together the struggle against inequality and the fight to save the planet in a way that I found to be very powerful.

Many worry that these two objectives of development and beating climate change are incompatible. If everyone on the planet is to live a healthy fulfilling life, then we will need to raise incomes to a level that is far beyond the ability of our planet to sustain. It is true that for everyone to live a good life in a privatised, neoliberal world, then we need to raise the incomes of everyone to a much higher level. If you have to pay for your education, your healthcare. If you have to pay to go for a walk in a forest or to access a playground for you kids. If you have to buy books instead of borrowing them from a library or buy a car because buses do not exist. All of this necessitates a higher level of per capita income which in turn necessitates a higher GDP and a use of carbon and energy that will destroy our world..

But this is not the only way to ensure everyone gets to live happy, fulfilling lives. Jason’s argument is that by going the public route, by providing services collectively and publicly, then we are able as humanity to live long, fulfilling lives whilst using a fraction of the earths resources than if we go the neoliberal route. Costa Rica for instance has a significantly higher life expectancy than the US but with less than a quarter of the per-capital income and a fraction of the environmental impact as a result.

I have always loved public services, for the profound expression of collective organised kindness they represent. Now it turns out they are also the key to saving our planet.

For now though, I am off to walk Marx in my quietly subversive local park.

Max is theHead of Inequality Policy at Oxfam International & EQUALS Podcast co-host. He is also Chair of the global People’s Vaccine Alliance.

Image Credits

Featured image: Marx at the park. Photo: Max Lawson

A cathedral of lime trees. Photo: Max Lawson

The chaos noise and density of the Kibera slum is neatly juxtaposed with the orderly calm green of the Royal Nairobi Golf Club, which opened in 1906. Photo Credits: Johnny Miller

"Anti-private health insurance rally. Saw a @laughingsquid sign in there somewhere, too." by kurafire is licensed under CC BY 2.0