The rise of Africa’s super-rich – Part 1

Soaring inequality on the continent is enriching elites and starving public services

Finance ministers from the 20 of the largest economies (G20) meet this week in South Africa, the first time an African country has hosted the meeting. There was hope that South Africa’s presidency would build on Brazil’s efforts last year to make a historic step towards taxing the super-rich. While a global tax agreement isn’t imminent, Spain, Brazil, Chile and South Africa launched a new global coalition at the Financing for Development Conference which focuses on taxing the super-rich.

Africa and its countries are among the world’s most unequal and its governments the least committed to reducing inequality, but they are also hamstrung by a debt crisis and unfair international financial and trade rules. Never was there a more important time for South Africa’s G20 themes of “Solidarity, Equality and Sustainability”.

In this week’s Bulletin, we look at Oxfam’s latest research into the rise of inequality in Africa which touched a nerve and led to widespread media coverage across the continent. Next week we will look at how Africa’s super-rich should be taxed.

Africa’s inequality crisis, in numbers

The rich get richer...The four richest men in Africa have more wealth than the poorest half of the region, about 750 million people. The income share of the richest 1% and 10% has increased since 2019 while the incomes of the poorest 50% have decreased.

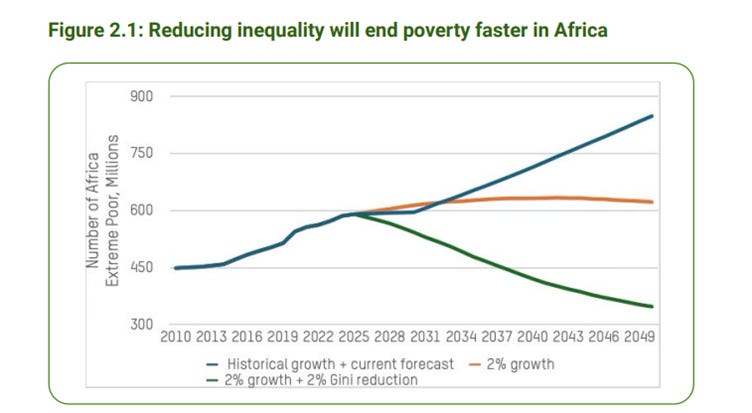

…while the majority are driven deeper into poverty. Hunger is rising in Africa, with 846.6 million people facing food insecurity in 2023, an increase of 20 million from 2022. High food prices are disproportionately hitting low earners, as they spend most of their incomes on food. Seven in 10 people living in extreme poverty in the world live in Africa, rising by 41.3 million since 2020. At the current rate, it will take more than 600 years to end extreme poverty in Africa.

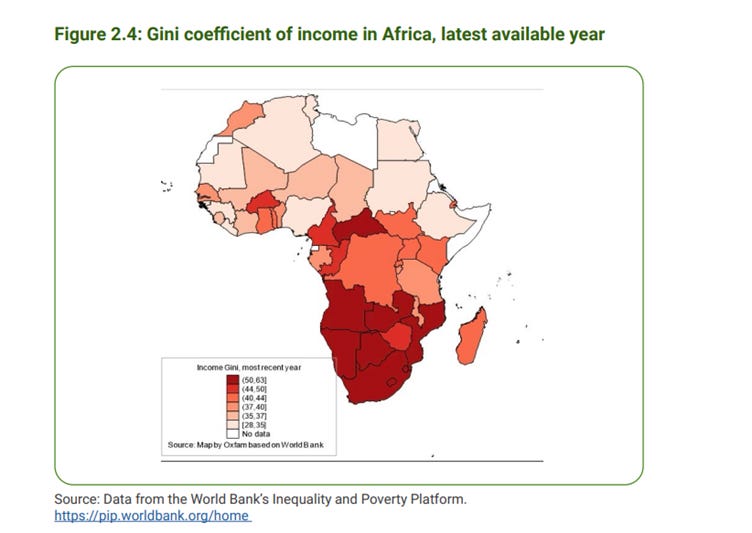

Soaring inequality. Almost half of the world’s fifty most unequal countries are in Africa and 44% of the countries defined by the World Bank as having ‘high inequality’ are there. Income inequality has increased or stagnated in 41% of African countries, representing half of the region’s population.

Billionaire bonanza. At the start of the millennium, Africa had no US dollar billionaires. Today it has 23, with a combined net wealth of $112.6 billion. Over the past five years, African billionaires have increased their wealth by 56%, the five richest African billionaires have increased their wealth by 88%.

Billionaire state support. Three-fifths of the world’s billionaires’ wealth comes from cronyism, corruption, abuse of monopoly power, and inheritance. This is particularly true in Africa. For example, Aliko Dangote, Africa’s richest man, was a beneficiary of the privatisation of publicly owned enterprises in the early 2000s, especially in the cement industry, and has subsequently benefited from tax waivers and tariffs. Dangote Cement paid an effective tax rate of 2% in 2016 despite net profits of 86%. Tax deductions for 6 Nigerian companies reached N5 trillion, accounting for 18.5% of Nigeria’s 2024 Federal budget.

This type of state support to billionaires and the super-rich while enforcing austerity has devastating consequences on the welfare systems which people living in poverty rely on.

Mind the gender gap. In Africa, men own three times more wealth than women; this is the highest gender wealth gap of all regions and is double the world ratio. The average length of paid parental leave is about 89 days (86 days of fully paid maternal leave and less than four days of paid paternal leave), which is low compared to other regions. A majority of the labour force is in informal employment, meaning existing laws do not benefit most working women in the region.

The debt crisis. The economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, and tightening monetary policy in the Global North have exacerbated the debt burden in Africa. Over half of African countries are at high risk of debt distress. Public debt as a share of GDP in Africa has more than doubled over the last decade to 67% in 2023.

Wave of austerity. The debt burden erodes governments’ capacity for social spending. Servicing the interest on debt alone is gobbling up 17% of revenue on average, double the amount a decade ago.

The poorest people are feeling the impacts of this; the richest people in Africa do not use public social facilities such as education or healthcare.

Case for inequality-busting policies. The African Union has recognised the problem of inequality. In 2024, it set its first target, to reduce inequality by 15% over the coming decade. If this target were met, Oxfam estimates that the rate of poverty reduction would be 2.4 times faster. Every African country has a Gini above 0.27, which IMF research shows slows economic growth. High inequality can lead to the rise of populism and the erosion of democracy. 60% of respondents surveyed across eight African countries thought that rich people buy elections ‘often’ or ‘fairly often’, which is significantly higher than in the rest of the world.

The lack of commitment to reduce inequality in Africa. The 2024 Commitment to Reducing Inequality (CRI) Index for Africa, which covers 48 African countries, shows governments are failing to introduce policies to fight inequality. The research found that all countries have cut the share of budgets going to either education, health and/or social protection, 79% have backtracked on measures of progressive taxation; and 89% have regressed on labour rights, minimum wage and the provision of quality jobs.

A few countries are implementing anti-inequality policies. Eswatini increased its spending on education and health, boosting social spending by 21% since the 2022 CRI. Benin is improving its social protection coverage, targeting 150,000 households with cash transfers and income-generating activities costing 0.2% of GDP per year.

Read Oxfam’s Africa inequality report here for all the details behind these numbers and subscribe now to receive next week’s Bulletin, where we’ll be setting out why Africa’s tax regime might look good on paper but in reality, is failing to fight inequality, and what can be done about it.

Something to read/listen to

Read President Lula’s oped in the Guardian about why we need true multilateralism.

Listen to the wrap-up of Season 7 of Equals, where Grazielle and Max reflect on their favourite and most impactful and powerful conversations from the season.

Read Mother Earth’s piece on how World Bank funded hospitals are detaining patients and leaving them with crushing debt. If you missed it, read our Sick Development report and listen to the podcast series on Oxfam’s investigation into the issue.