WHEN NEOLIBERALISM TOOK ON AFRICA’S ECONOMIC IMAGINATION – With Zambian Economist Grieve Chelwa

By Elizabeth Njambi

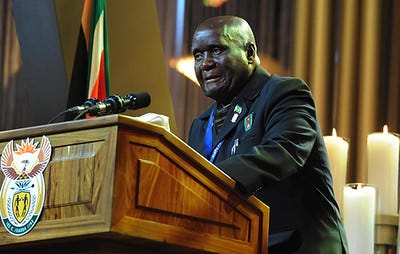

Former Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda (“KK”) – who led his country in the wake of independence from colonial rule – recently died. A pan-African giant, he pursued efforts to boldly pursue equality at home and fight for liberation across the African continent.

Max Lawson and Nabil Ahmed have an amazing chat with Dr. Grieve Chelwa on what President Kaunda really set out to do with the state taking a far more active role. What can we learn from “Kaundanomics” for today? And what was the impact of the defining “structural adjustment” period on Africa’s economics?

This is the first of a two-part special diving deep into African economics. This episode takes us back. The next episode looks forward.

Dr. Grieve Chelwa is the Inaugural Postdoctoral Fellow at The Institute on Race and Political Economy at The New School where he leads the Institute's work on Inclusive Economic Rights. He was formerly Senior Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Economics at the University of Cape Town's Graduate School of Business and before that was the Inaugural Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for African Studies at Harvard University. Before taking up a career in academia, Dr. Chelwa was a banker with Citi and completed postings in Congo (DR), Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa.

If you’re joining us on EQUALS for the first time, tune in to our earlier interviews – from talking with the award-winning journalist Gary Younge on what we can learn from Martin Luther King Jr to fight inequality, to best-selling author Anand Giridharadas on whether we need billionaires, Zambian music artist PilAto on the power of music, thinker Ece Temelkuran on beating fascism, climate activist Hindou Ibrahim on nature, and the Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund Kristalina Georgieva on what comes after the pandemic.

A little about Dr. Grieve

Max: [00:03:28] So Grieve, really, welcome to the podcast. It's great to have you on. For the benefit of our listeners, could you just say a little bit about your yourself?...

Dr. Grieve: [00:03:40] Okay. Thanks Max. So, my name is Grieve Chelwa. I'm an economist who comes from Zambia. I'm talking to you right now from Lusaka, Zambia. I trained as an economist at the University of Zambia and the University of Cape Town. Subsequently, I did a posting at Harvard as a post-Doc researcher there. Taught at the University of Cape town at the business school.

And now I work at the Institute on Race and Political Economy at the New School that was started this year and is directed by Darrick Hamilton, your old friend.

The Late President Kenneth Kaunda (“KK”)

Nabil: [00:04:07] … You're a bit of an expert on former Zambian president, Kenneth Kaunda, and his funeral was held just a few days ago. It's prompted I think a lot of reflection on his legacy and on the legacy of other leaders in Africa from the past. … Could you tell us a bit about former Zambian president Kaunda and you also wrote about Kaunda-nomics if I've said that correctly. Could you talk us through that?

Dr. Grieve: [00:04:39] Yes. So, Kenneth Kaunda was Zambia's first President. So, when Zambia got independence from Britain in 1964, he was the first President of the country. He was President from 1964 up until 1991. So, as you can imagine, he had a very big impact on … the country Zambia and the idea of Zambian identity and Zambian nationality. …

We've always thought as Zambians that he is under-appreciated globally, but I think it's very interesting to see although belatedly after he's died, …, this sort of continental and global recognition or rediscovery of Kenneth Kaunda.

When you talk about the piece that I wrote for Africa as a country in 2017, actually in commemoration of Kaunda's 94th birthday, if I'm not mistaken, basically what I wanted to write in that piece was to remind Zambians, (and) Africans on the continent and even the world; that we had a different kind of economics in the post-independence era. That kind of economics is forgotten now. It was swept up in the tide of neo-liberalism. … I want to remind folks about that era and just the achievements of that era.

Nabil: [00:05:50] … What are the policies that he had post-independence? How progressive were they? What was it all about?

Dr. Grieve: [00:05:59] So, what is very surprising to most people is that at independence, Zambia was pretty much, sort of following free market capitalist type of policies because he believed, and I think he might've been advised, that that was the best way to organize the Zambian economy to deliver development for everybody.

… (But) in the first couple of years …, he realized that the economy,… was really in the hands of a minority white capitalist class, … The private sector, which was driving the economy, wasn't really participating in this process of economic development, which was so vital given that a big chunk of the population was poor. So, he immediately realized we need to change course.

… He announced some major reforms. Sort of nationalizations of, …the private sector. 80% of the economy subsequently transferred into State hands, and this launched a route (of) rather ambitious economic development program which, (to me), worked in so far as developing infrastructure; building roads; hospitals; ensuring that Zambians were progressing through the professions; ensuring that there was social mobility; ensuring that there was a reduction in economic inequality: all these kinds of things. So, really Kaunda was not an idealogue, but really his economic policy was motivated by material conditions on the ground.

Where would Africa be Today?

Max: [00:07:24] I suppose it's this idea of state involvement that has been completely forgotten. And I wondered ... where do you think Africa would be today, Grieve? If we hadn't had that neo-liberal moment, if we hadn't had structural adjustment, what are the kinds of things that we could be seeing today that we're not?

Dr. Grieve: [00:07:42] … You're right, Max. That it was realized in the 60s and 70s, that you cannot develop without having an active state, right? It is impossible because when you leave everything to the market, ... the market doesn't have feelings; doesn't have emotions; it doesn't have humanistic objectives…All you're going to do is really just capacitate the already well-off, which in the Zambian case was sort of a minority white capitalist class. You see it across much of Africa at this point because there was this recognition that we really need to direct the resources of the state, otherwise we will only have a small minority that is doing very well.

… If structural adjustment hadn't happened, we would be in a far better position. The things that we care about: poverty & inequality, I would argue these things which have now began to rear their very ugly heads in the African context would not be there. We would have much, much more social mobility than we currently have.

I always like to tell the story of my father. He was born in a very rural part of Zambia. Cattle herder who ended up at university and, uh, you know, and completely went up the sort of social hierarchy. These kinds of stories are few and far between now. So, I think this is where we would be today if we hadn't done structural adjustment in the way we did it.

“Pan-Africanism Bankrupted African States”

Max: [00:08:57] Oh, I, I completely agree. What about the 'challenge' if you'd like, Grieve, to the kind of Pan-Africanism or the African socialism of Kaunda or Nyerere that it basically bankrupted their countries. It was a great idea, but it was just not affordable. So structural adjustment was the 'necessary medicine'…

Dr. Grieve: [00:09:28] … Misdiagnosis of the problem. What we need to understand is what caused the crisis in African economies beginning say, late 70s, early 80s, and my reading of the evidence, at least the careful reading of those who've done careful work on this, suggests that the cause was really external factors. …

And I think the solution was the wrong one because the crisis was misdiagnosed. The solution by the IMF and World Bank, which led much of this policy work was to identify a majority of the crisis as being internally generated. So, therefore, structural adjustment was a wrong solution to the wrong problem. In actual fact, what this country really needed was foreign exchange.

The Reaction to KK’s Policies

Nabil: [00:11:09] ... What was the reaction both at home, but also from abroad, to the measures that KK was taking? It's very easy looking back now for people to, with hindsight, positively remark on achievements in that period but that can't have been the same at the time.

Dr. Grieve: [00:11:39] … One interesting anecdote that I can share with you is that just after independence, uh, Kenneth Kaunda visited one of the mines. At this time now, the mines are still privately owned by American Metal Climax and Anglo-American. Uh, it's a topic for another day how it is that Anglo-American and American Metal Climax but we'll leave it at that.

So, the mines are still privately run and then KK visits one of these mines and he looks around the managerial class. And he sees that there are no Zambians in the managerial class. This is about maybe early 60s... And he asks, "So, when can we expect, (if) business is business as usual,… When can we expect to see Zambians, taking over some of these managerial positions?" And with straight faces, the white owners tell him, “Not before 2003, Your Excellency!” And that's the problem with private sector because private sector is always comfortable with business as usual. They can justify anything. And you know… in a matter of years, we had lots of Zambians taking up very senior positions here and there who have gone on to a very illustrious, distinguished careers in the mining sector globally. ...

The response back home was very receptive because this is something that the people who had fought for independence saw as a necessary thing.

The response outside, on the other hand, was very critical. I've read some cables, for example, from the law firms that were presenting American Metal Climax, Anglo-American and these other kinds of places really writing about how ‘these guys should be treated with care. They might be radicals. We have to be very careful’. So, the external reception was very cold. Luckily for us, the reaction was not as bad as it was in Chile. As you know, at the time when nationalizing our mines, Salvador Allende, who was Present in Chile, also nationalized the Chilean copper. And ..., the rest is history in Chile. Three years later, Allende was murdered.

Max: [00:13:47] We could have had a Zambian Pinochet.

Dr. Grieve: [00:13:49] You know? Exactly. So fortunately for us, maybe Zambia wasn't so important for the US and whoever was involved in the Chilean coup. …

We use this word nationalization very carelessly. We did not take over these minds without compensation actually. Kaunda ... and his government just took a 51% stake. So, American Metal Climax and Anglo-American Corporation still maintain some stake in the mines and they were actually compensated for the 51% stake that we took over by issuing very costly bonds that really saddled us with debt. So, it's a very ironic situation, where Zambians have been paying debt to get back mines, which were supposed to be theirs anyway.

Kaunda and Southern African Liberation

Nabil: [00:14:32] I feel we could talk about KK all day. I'm interested just to ask you about his role, more widely on the continent in supporting liberation struggles. If you could talk us through that, but also to what extent was it a distraction from what was needed to be done at home in Zambia?

Dr. Grieve: [00:14:50] Thanks for that question. KK is a student of Kwame Nkrumah's notion of African union and African liberation and African independence. I think he attended the very famous, All Africa People's Meeting that took place in Ghana in the late 50s, just after Ghana's independence. Nkrumah did say on the occasion of Ghana's independence in 1957, that it's pointless for,… I'm mis-paraphrasing him, but he said something to the effect that it is pointless for us to celebrate independence if the rest of Africa is not liberated.

So, KK was a graduate of that school of thought. And it is not surprising that within Southern Africa, then he began to say, "Look, I mean, it is pointless for us as Zambians to be this island of independence when those around us are still fighting white minority rule." So, he then took a principled stand to say he is going to support liberation efforts. Many of these liberation movements had some representative representation in Zambia. They had a home in Zambia. I think the ANC even had a headquarters in Zambia.

Max: [00:15:51] I think actually, Oxfam shared an office with the ANC in Zambia for 20 years, I think... We have a distinctive history and we had all of these kinds of so-called projects that were actually just support for the ANC. …

Dr. Grieve: [00:16:14] … I'm very jealous for my parents' generation because they have stories from that era. Seeing Thabo Mbeki on a Lusaka street or Jacob Zuma somewhere there, but these things are not free.

I can only imagine hosting people who are engaged in waging a war. It must not be a very cheap exercise. So even when our Copper fortunes are dwindling, even when Kaunda has this mammoth task of developing the country, he had to think about what was happening elsewhere. So, in terms of economic resources …

Max: [00:16:48] And all sorts of destabilization. I mean, who knows what the South Africans were up to and the Rhodesians, you know, in terms of trying to undermine the Zambian economy the whole time.

Dr. Grieve: [00:17:00] I can only imagine the kind of nefarious things that were going on. And Max, this is a very important point you raised because to my mind, a proper reckoning of what happened to many African economies in the 60s, 70s and 80s has to grapple with what you just talked about. Geopolitics. Sabotage. Economic sabotage, … these things can be just as destabilizing as anything else. So, I think for many Zambians there's this sense of what could have been, right? Imagine if KK had just focused his energy and resources on developing the country.

COVID Recovery for Africa

Max: [00:17:39] If we kind of fast forward to today. So, we've had this coronavirus calamity that is building on an existing debt crisis in Africa. And, you know, we've just done work as Oxfam looking at IMF programs for the next 4 or 5 years. And I mean, maybe it's not the full gloves-off structural adjustment, but it's not fun far off. I mean, it really is about massive fiscal consolidation. And in some ways, it isn't all about privatization because those things have already happened, you know? So, it's not because they've somehow realized that they don't need to do that any longer. It's no longer a big state to chip away at, but where do you see the kind of resistance to that economic worldview in Africa in the next few years? And what can we do to build a different economic model and a different recovery from the COVID crisis?

Dr. Grieve: [00:18:32] Coronavirus crisis has exposed this aspect that the economic policies of the 80s (that) really eroded the state were completely disastrous and for me… the most important thing I think in the African case is to build back the capacity of the African state. Really make it much, much bigger than it is; much more present in the economics aspects of spheres of people's lives.

So not so much to reinvent a different economic model. … We'll have the blueprint from the immediate post- independent years. We need to go back to that era, learn what worked, adapt what didn't work...

The problem is really for us to be with a capable, effective state. And this is why we're completely being annihilated by the coronavirus crisis. That is why it's completely impossible, and difficult for many African governments to control. For example, you know, issues lockdowns, partial lockdowns, because I mean, people need to eat.

People really exist outside of the state. People are eating out, living in the informal economy under very bad conditions. And that in itself - the informal economy is not natural. It doesn't happen. Didn't happen just like that. The informal economy begins to happen when the state has been brought back in the 80s. So, …this coronavirus crisis has really brought home the lesson of having a capable State.

African Solutions for African Problems

Nabil: [00:19:53] Very interesting Grieve. To what extent have the challenges that we face on the African continent today, been a result of just in a colonial way, importing foreign economic models onto the continent? And Grieve … I was also interested to see in your bio that you have also experience as a banker with some prominent Western firms. So, you've seen it from the inside as well.

Dr. Grieve: [00:20:18] Yes, I have. I've seen it from the inside so, in many ways ... I'm like the atheist who's read the Bible cover for cover if I may use that kind of example. I think ...the issue about homegrown African solutions for me, it's a red herring. What we need to do is to learn from everybody. Learn, for example, if somebody has to say what you learned from the US? I mean, I would say the lesson there is that, you know, building a capitalist behemoth on the basis of slavery is not the way to do it, right?... So the point is to say, we need to learn from everybody else who's come before us, right? And then adapt those learnings for local situation. And then to drive that process. And this is why for me, the immediate post-independence era, if I had to do research, a book project on it, I would study it very closely because therein you see the lessons of saying, "We're now independent. We want to develop. Where are we going to look? Okay. Let's look over there. What are they doing? Right. Okay, they're doing that right. What about over there? What are they doing wrong? They're doing this aspect wrong". And then we're in the driving seat. And you see this in the KK era.

For example, we had development plans. We had four development plans between 1966 and 1989. And then when the structural adjustment era came with the new government, we stopped planning completely. I mean, so one is left to wonder what was happening during that 15 years. But so, but that is exactly for me the issue... We need African solutions for African problems. I think what we need is Africans to drive the process, but we need to learn from everybody else. We need to be engaged in discussion, in conversation with others so they can share with us their lessons, their failings, and their successes. That's the way to go, I think.

African Inspiration

Nabil: [00:21:58] Wonderful. We've spoken about that era of leaders, the school of Nyerere and others, as you so nicely put it before Grieve. I'm interested to ask, who's carrying the torch of that legacy today in Africa? Are there countries on the continent that you look to and say, yep, that's, that's the way to go? You know, who's doing things right?

Dr. Grieve: [00:22:18] I've been thinking hard. And I can't think of any, to be honest, um, because structural adjustment was really profound in its impact in the realm of ideas. Um, one of my intellectual heroes is a Malawian economist called Thandi Mkandawire and he wrote an essay about ideas. Important ideas in the economics spere and just the kind of just how, how we ended up with these different ideas about how to organize the economy and what you have right now running affairs in many African countries, are men and women who got their training in the 80s at the height of structural adjustment.

So, if you are trained as an economist in the 80s, just imagine the kind of training you received and, you know, once you are trained, it's difficult to be untrained. You have to run with those ideas. But for many of the many parts of the continent, we have people who really believe in the private sector. Who worshiped at the altar of the market. And that is why we're seeing all this inequality popping up... it's mine. I mean, I've been, I've been back to Lusaka now for the first time in 14 years for an extended period of time. And I mean, the houses I'm seeing; the lifestyles I'm seeing are incredibly crazy.

So I cannot think of any country to be honest, maybe Botswana comes close. I mean, Botswana is always touted as a success story, but Botswana is also very unique in that it's, um, a very uniform country, then small country, the huge resource in government, but even then they've managed it well. But I cannot think for example, of a country that stands as a model now. I think there is a lot of traction like you are saying. There's a lot of young people now who are beginning to discover that period. And then we're beginning to think about crafting, imagining a new way of organizing things going forward.

Max: [00:23:57] Just one thing you said there Grieve... So you're coming back to Lusaka. When you say that the houses, (are different) did you mean the scale of any inequality? It feels more dramatic. What did you mean by that?

Dr. Grieve: [00:24:10] Yeah, it is very dramatic. I think one of the things we haven't done very well in the African case is to carefully document the inequality and the kinds of inequality that have arisen since structural adjustment.

I mean, it is quite profound. I am seeing people living lifestyles that, uh, you know, were once the preserve of, you know, the Uber wealthy, many of these financial capitals of the world and it's happening here in Lusaka. Right? But then it's happening at a time that a lot more people are being left behind. There's a lot of immiseration.

So, this kind of in-your-face inequality that I have seen in Lusaka and I'm sure it's the same everywhere else. Max, I'm sure you've seen a change over your own a long career. I mean, it's the same if you go to Nairobi. It's the same story.

Max: [00:24:53] Even in Malawi. You know, the scale of the inequality seems to me more, more dramatic. Definitely. And I think Africa is still seen very much as a poverty problem. Not as an inequality one, you know? And I think that's problematic.

Dr. Grieve: [00:25:10] That's true. And when inequality pops up like this, then, you know, things like democracy and, you know, and ballot box democracy and elections and political parties almost always become like a farce because you know, those who are very well off. Who are like (as) Max put it who are you know, deriving rents from this kind of status quo. I mean, they have to defend that status quo. So yeah... it's crazy.

Nabil: [00:25:35] Let me end grieve with a question about hope, because we've covered a lot of history over this podcast. We've also looked at the present day. With the, it feels like insurmountable problems at times, but do you have hope for you know, a real progressive, a real sense of greater economic equality on the African continent?

Dr. Grieve: [00:25:56] I think I do. ... When people think about structural adjustment, they always think about it in economic terms, but it had economic and political ramifications. ... There's something in this new generation that has sensed the failings of what has happened the last 20, 30 years and we are trying to sort of rediscover, you know, our history. So I'm very hopeful, uh, that you'll see more of these progressive parties, more of these progressive formations.

Max: [00:26:45] Or just more ideology. I mean, one thing that's always been lacking, it seems to me, (you) just don't see the kind of Left-Right discussions. It's all about kind of transparency and corruption and all very important things, but no kind of ideological construct. And so do you think that's perhaps changing? Cause that would be exciting.

Dr. Grieve: [00:27:06] I think it is changing seismically in the new generation, but obviously we need to do the work and you're right Max in your observation, but this is what structural adjustment did. It won. It was settled. I mean, there was a whole infrastructure that subsidized the idea so you'd have to be crazy about 20 years ago in civil society saying, we need to go back to Left-leaning politics or Left-leaning policies. People would laugh at you. Well, the result is here. Mass starvation, hunger, unemployment. So you're trying to, you know, so, but I think we now realize that, oh my God, the story ... was taught wrongly. You know? Well, I can see, for example, the likes of PilAto, for example, and many other people who are articulating, talking about inequality and the inequality rearing it's ugly head. These kinds of conversations were few and far between 10 years ago.

Nabil: [00:28:00] Thank you. Thank you so much Grieve for this interview. We have a rule for like 30-minute podcasts to keep them in a digestible format, but I feel this one could have gone on for hours. So thank you very much, bro. And thank you for everything that you do.

Outro

Max: [00:28:28] Wow. That was like catnip for me. I mean, African history. Left-wing politics. I mean, oh, it was brilliant. I loved it.

Nabil: [00:28:35] And clearly we need to do more history on the podcast, Max.

Max: [00:28:38] Totally. Yeah.

Nabil: [00:28:38] There were many amazing points that Grieve made there as well. I think his points about, you know, the sheer death blow of structural adjustment were very powerful. It hit public services. It hit at the State, but also economic imagination here on the continent.

Max: [00:28:51] Yeah. I mean, it's something I've also studied a lot over the years and it was such a period of ideological experimentation. You know, if you imagine how they privatized Russia after the Soviet Union fell, it was exactly the same.

You had these kind of right-wing economists working for the Bank and the Fund arriving in a country like Zambia, seeing it like an economic experiment and they had such power and they did so much harm to so many people's lives. And it's important to understand that legacy, but also it's so relevant to the lack of policy debate today.

Because as you say, they kind of limited the imagination of what's possible.

Nabil: [00:29:28] Yeah. And there is this assumption, I think sometimes in my generation, Max, that Africa's always been the same. But the truth is, you know, we've had different economic models over the last 50 years or so. And it's very interesting today, speaking to Grieve, you know, how 20 or 30 years ago, you'd be laughed out the room, talking about the role of the State, but that is now happening.

There is this willingness to embrace some of the ideas from the past, from that post-independence period, isn't there?

Max: [00:29:51] There is. And I think it, you know, it's not even a left wing thing. You know, the idea that your government should actively be involved in the development of your country. I mean, look at the history of someone like Taiwan or Korea.

Basically any country on earth. Rich countries, you know, had big, big involvement of government. So it's great to see that that's back on the agenda for Africa because Africa will not develop without it.

Nabil: [00:30:15] And there is some hope, isn't there, from some leaders, Max? Because Grieve gave us a challenging answer here, but you look at Julius Maada Bio, the President of Sierra Leone, there are some leaders with imagination trying to equalize things.

Max: [00:30:27] I think there are. And we've certainly talked about them on the podcast before, but I also think there are many leaders in Africa, many governments in Africa, who do not have the interests of the people at heart. And that in itself is a product is, as he talked about, the grotesque inequality, the kind of marriage of money and politics, which is not just an African phenomenon. We see it in the US we see it everywhere. And that leads you to a situation where you kind of, on the one hand, you want to see governments do more, to develop the country. You don't want to leave it to the free-market, but on the other hand, you look at your current government.

I mean, imagine, you know, the current Kenyan government having the same vision of Kenneth Kaunda, developing Kenya. It's hard to picture, isn't it? So I think that is the big dilemma, not just for Africa, but for everywhere.

Nabil: [00:31:13] Yeah, I think you're right there. And that's a tension that we get into in our next episode. It's also an amazing episode with Crystal Simeoni based here actually in Kenya. She will be walking us through what an economics looks like for the future in Africa, and also critiquing some of the things that are wrong with mainstream economics, that it doesn't get about Africa.

Max: [00:31:31] Yeah, that is going to be great. Coming to the future and what this means right now for Africa. It's going to be a great episode.

Nabil: [00:31:37] Thanks everyone for joining us. Do leave us a review, share the podcast with your family and friends and do join us next time.

Max: [00:31:43] Yeah. See you all next time. Cheers!

Elizabeth Njambi is the Producer of the EQUALS Podcast. She also manages the EQUALS Blog. Elizabeth is a Kenyan Advocate passionate about access to justice. She is the Founder and CEO of Wakili.sha Initiative and Co-host of the Wakili.sha Podcast.

Image Credits: The Late President Kenneth Kaunda "State Funeral of former President Nelson Mandela, 15 Dec 2013" by GovernmentZA is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0