Two drops of life: for me – and millions like me – aid has been a gamechanger

By Anthony Kamande

Anthony Kamande still remembers the aid-funded polio vaccine he received at his Kenyan school at the age of eight. As such transformational aid is abruptly pulled across Africa, local governments cannot plug the gap, he says – much as we would like them to. Without a turnaround in aid policies, much of the continent faces a bleak future of surging health inequalities and rising poverty.

If there is one thing that I remember vividly from my childhood, it is the two drops of oral polio vaccine I received at the age of eight one Saturday morning at my Kenyan primary school.

Polio is an infectious virus that paralyses body parts and can lead to death. It has no known cure yet, but it is preventable through vaccination. That jab, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), ensured I and so many others never got it.

Aid has been a gamechanger

Aid has its critics but what is undeniable is that, despite all of its ills, aid has been a gamechanger in Africa. I have benefited from it personally, not just through polio vaccination but through primary school feeding programmes. I see every day how it is helping thousands of poor children in Kenya stay in school or access nutritious meals, and people living with HIV access antiretroviral (ARV) medication.

It is easy to make blanket criticisms of aid if your public healthcare system is working for you, if you have the money to buy private healthcare or if you do not have to worry about whether your kids will go to bed hungry. For many of us, it has been a matter of life and death. It has saved lives and prevented life-long illnesses like polio.

Aid intervention in Africa has contributed hugely to health outcomes that have significantly improved since 1990. Women and children have reaped immense benefits. The child mortality rate in Africa per 100 live births has decreased by three-fifths since 1990, while the rate of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births has halved. On average, an African now lives 12 years longer than in 1990. Communicable, neonatal, maternal, and nutritional diseases – where most foreign aid in Africa is directed – have seen considerable reductions.

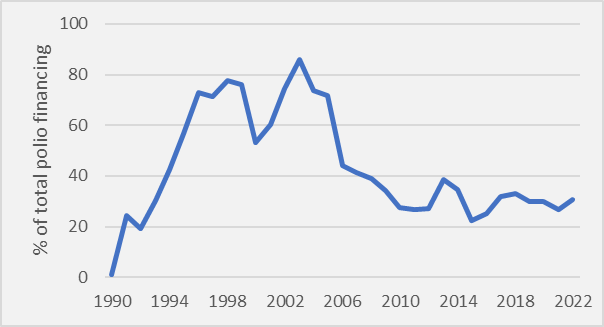

And it’s not just my own continent: since 1980, the global campaign to end polio has led to a sharp decline in polio cases. All countries except Afghanistan and Pakistan are now polio-free. Official Development Assistance (ODA) has been at the forefront in ending polio, accounting for the biggest share of polio funding in poorer countries, especially between mid- 1990s and 2000s.

Fig 1: G7 countries and European Commission financing towards polio

Can’t local governments do more?

Why do we still need foreign aid? Can’t countries look after their own people? It’s true that for many decades now in poorer countries, governments' investment in healthcare, including lifesaving vaccinations, has been grossly insufficient. Scarce revenues, lack of political and policy commitments, and frequent economic shocks have been at the centre of this.

Though extremely inadequate, domestic resources have played a big role in healthcare and other public services and cannot of course be replaced by aid; in fact, they need to be increased dramatically. An while important to ensure access to lifesaving drugs, aid can also play a role in supporting a country build its own public healthcare system. I need to see my government investing more in public healthcare. I would have loved it if my government had funded my polio vaccine, as it should have done.

But starting to change all of this takes time: the sheer abruptness of recent aid cuts from rich countries has left governments and people with no room to look for alternatives.

And there are other huge barriers beyond local policy choices: notably, the greed of big pharmaceutical companies and stringent intellectual property rights that inhibit access to lifesaving vaccines and medicines. There is also the massive burden of repaying international debt, which swallows up a huge proportion of revenue that could otherwise be spent alleviating poverty.

Given these constraints, we simply cannot wish away the current need for aid in improving the public healthcare system in Africa, saving lives and preventing suffering.

And foreign assistance is a tiny proportion of rich-countries’ GDP

And of course, while lower-income countries face huge challenges raising revenue, a small share of rich countries expenditure can deliver immense benefits to poor people in poorer countries. ODA accounts for less than 1% of total government expenditure of official donors. In absolute terms, the US has been the main ODA donor globally. In 2023, it accounted for 29% of total ODA. However, this accounted for only around 0.6% of US government total expenditure in 2023.

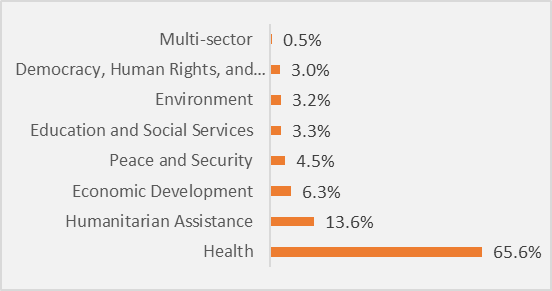

Healthcare has been the single biggest beneficiary of such US foreign assistance to Sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 3). In 2023, it gobbled up two-thirds of total US aid. In 2023, American foreign assistance to Africa was equivalent to more than half of the total government expenditure on health in Africa while using up only a tiny fraction of American government spending.

Figure 2. ODA as % of total government expenditure, 2023

Fig 3: US total foreign assistance in Sub-Saharan Africa by sector (2023), %

Now, cutting the tiny fraction spent on aid will be devastating

The abrupt cuts mean immediate impact on millions of poorer people, particularly women and children living in poverty. Tens of thousands of the most vulnerable face deaths, suffering and life-long implications. It's not just the US: other governments are announcing cuts in foreign aid, under the guise of shoring up defence spending. The UK government will cut its already low ODA by 40% to increase its defence budget. Other European countries, including France and the Netherlands, have announced similar measures.

Here in Kenya, the impact of the US aid freeze is already being felt, with more than $800 million worth of contract terminated. Thousands of people living with HIV/AIDS are worried that their health and financial situation will worsen. The freeze means they will be forced to dig deeper into their pockets to access the lifesaving ARV drugs, which they have been getting for free thanks to aid. However, many live from hand to mouth and will be forced to make grim choices on whether to die of hunger or HIV-related complications.

Rich countries should target the rich through tax, not the poor through cuts

Governments have the right to secure their citizens at a time of most heightened geopolitical tensions since the end of the Cold War. However, cutting aid budget to increase defence or any other spending is cruel to the most vulnerable people, and to the very least defeatist. As I say above, cutting aid does not save a lot given how small a small share of national budgets it takes up. What’s more cutting it will not strengthen national security: it will make everyone unsafe as poverty and instability grows.

Instead of cutting their meagre aid budgets, rich governments should be looking at the enormous amount of money in private hands and introduce progressive taxation on the richest. For instance, Oxfam has calculated that a progressive wealth tax on the EU’s multimillionaires and billionaires could raise nearly $300 billion annually, an amount that is a third more than the total ODA disbursement in 2023.

A sudden change of policy that will create chaos and suffering

The sudden nature of the cuts is particularly destabilising: US foreign assistance had been on the rise until it disappeared overnight. In fact, for two decades, between 2001 and 2023, US foreign assistance to Sub-Saharan Africa more than quadrupled, from $3 billion to $12.4 billion at constant prices. In 2024, a third of the total US foreign assistance disbursement went to Sub-Saharan Africa, up from 12% in 2001.

Fig 4. US Foreign Aid Disbursement to Sub-Saharan Africa

Fragile and conflict-affected countries, as well as the poorest countries, will be the worst affected by the freeze. In 2023, US foreign assistance accounted for more than 10% of the total expenditure of ten countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, with Somalia, South Sudan, Central Africa Republic, and Sudan taking the lead.

Reversing years of gains, worsening health inequalities and increasing poverty

Despite progress, Africa is still far away from the health outcomes of rich countries. Only the rich have the means to get the best healthcare and nutrition. The child mortality rate is still two times higher than the global rate, and about 200,000 women in Africa die each year because of pregnancy-related complications. In 1990, Africa accounted for 43% of the global maternal deaths; it now accounts for nearly three-quarters (73%). Half of these deaths are in two countries alone- Ethiopia and Nigeria, the biggest and the third biggest recipients of US foreign assistance between 2001-2024. Today, a European can expect to live 15 years longer than an African.

Cutting foreign aid will worsen the region's health challenges, reverse the gains made over the decades, increase inequalities in access to healthcare, and worsen health outcomes. It will also worsen poverty. By next year, the US aid freeze could push an additional 5.7 million Africans into extreme poverty, and 19 million more by 2030.

Protecting aid is in all of our interests

Unless rich governments move quickly to reverse foreign aid cuts and freeze, the whole world could pay the price, Obviously, the biggest burden will be on poor people in poor countries but contagious and communicable diseases like Ebola or new ones like COVID-19 will become difficult to detect and contain, reaching every corner of the world. The fallout from increased instability and conflict too is rarely contained within national borders.

None of this needs to happen: rich governments can both protect and increase aid budgets and balance budgets by taxing the wealthiest as they have done before. Instead of cuts, poverty and disease, we could have revenue mobilisation through progressive taxation and boosted social and health spending in poor countries. That would guarantee that every child in the future gets the vaccine they need – just like I did.

Author: Anthony Kamande is Inequality Research and Policy Advisor at Oxfam International.

Read our latest bulletin on role of central banks in shaping inequality and listen to our latest episode on central bank policies and impact inequality.

This blog is also published in the Views and Voices and Policy and Practice